It was a hot summer afternoon in a village in central India. A man lay on a string cot in the shade of a mango tree while his two sons played marbles. We approached him with hesitation. “We are making a village report card of schooling and learning,” we said tentatively. “Can we ask your sons to read?”

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) reading assessment tool we were using requires that children perform a few tasks: recognize letters, read some everyday words, read a few sentences, and then read a short, eight-to-ten-line story. The story is the highest level in the reading tool, pegged at a grade-two level of difficulty.

The man looked at the tool and declared, proudly, “I send my children to school—a private school.” The younger son was curious and came forward to read. He was enrolled in third grade, but he struggled—he could barely get past sounding out the words. The boy’s father sat up on the cot and called over his other son. “This one has just finished primary school,” he said. The older son abandoned his marbles and concentrated on the reading. According to his father, the boy had just completed fifth grade. He could decode words, but the sentences were hard for him, and the short story was much too difficult. By this point, the father was on his feet. “How is this possible?” he demanded. “My children go to school.”

Schooling vs. Learning

Until quite recently, the world has been busy making schooling universal. We have built schools, hired teachers, procured textbooks, and enrolled children. Most people have assumed a direct correlation between years of schooling and amount of knowledge. Even in academic circles, years of schooling has long been a proxy for education. In India, for almost 10 years, 95 percent of elementary school age children have attended school, and more and more children are staying in school longer. A decade ago, 12 million Indian children were enrolled in eighth grade; today, there are close to 25 million.

But does schooling automatically mean learning? Data from many countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa suggests it doesn’t. Since 2005, for example, ASER reports on India have shown that only about half of all students in fifth grade can read text meant for children in second grade. Simply put, this means that five years of schooling doesn’t even translate to two years’ worth of learning for more than half of all children who have come that far.

ASER survey reading tasks in Hindi.

ASER survey reading tasks in Hindi.

Recognizing this challenge is an important first step in developing more-effective education, but for many people, first-hand evaluation is essential to “seeing” the problem.

A young fourth-grade teacher who recently used the ASER reading tool to assess his students said to me the other day, “I did not believe the reports in the newspaper. Of course, I knew that some children were not doing so well. But when I tested the children in my own class, I suddenly saw the depth of the actual problem. More than 40 percent of my children in the class could not read simple things, so I was wasting my time teaching them from the fourth grade textbook.” For this young teacher, the assessment tool helped him see reality in a concrete way.

Learning: The New Goal

Assessments like these—ones that are easy to administer and understand—empower ordinary people and parents, educators, and policymakers to align around a new goal: learning.

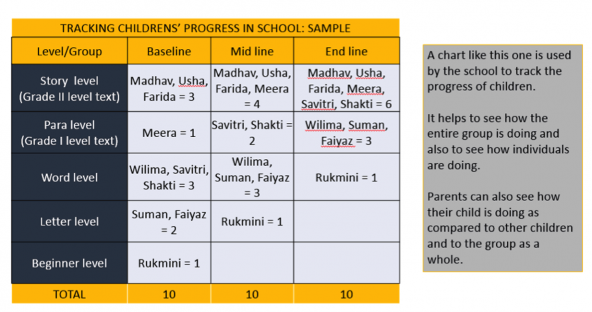

Armed with information about each student’s ability to read, for example, teachers can put students into groups with others at the same level. Teaching at the “right” level—by ability, rather than by age or grade—enables children to progress more quickly. The ASER reading assessment we use feeds directly into grouping for instruction, and offers activities and materials designed for each group. For example, children who do not recognize letters play letter games; those who can read words do activities with sentences. Measuring progress periodically helps the teacher, the parents, and the children understand how far they have come—how much they have actually learned.

“Report cards” track progress in reading for a group of children.

“Report cards” track progress in reading for a group of children.

For 10 years, the ASER report in India has produced estimates of basic reading and arithmetic for a representative sample of children at the district, state, and national level. The ASER survey is a household survey; it assesses basic reading and arithmetic. It reaches more than 600,000 children in over 16,000 villages through 25,000 volunteers from 500 plus district-level organizations and institutions. This unique model of citizen-led assessment has spread to Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Senegal, Mali, and Mexico. Both in India and globally, efforts like these have enabled communities to look beyond schooling to the crucial importance of building the foundations of learning.

Once his sons learned to read and do arithmetic, I am sure their father went back to lying in the shade of the mango tree. But I am equally certain that his eyes remained wide open and watchful. He needed to ensure that his children, like many other children in India and elsewhere, were in school and learning well.

Dr. Rukmini Banerji is the CEO of Pratham and Non-Executive Director of ASER Centre, India. She is also the founder of citizen-led assessments and Advisor to the PAL Network Steering Committee.

Origninal blog posted in the Standford Social Innovation Review on 27th February 2017.