By PAL Network’s Research Team

Introduction

Foundational learning skills form the cornerstone of human capital development (UNICEF, 2020). Yet, nearly 60% of children worldwide are unable to read and comprehend a simple text by the age of 10—a stark indicator of a global learning crisis (World Bank, 2022). In response to this urgent challenge, the PAL Network launched the My Village program in 2022, with the goal of supporting one million learners over five years to strengthen foundational skills in literacy and numeracy. The program is built around four interrelated components:

- Accelerated Learning Camps (ALCs), where children are grouped by learning level rather than age or grade;

- Community libraries, which encourage children to read and borrow books;

- Short Messaging Service (SMS), used to engage parents in their children’s learning journey; and

- Life skills sessions designed for adolescents.

As of February 2025, the PAL Network, in collaboration with its member organizations, has completed two phases of the My Village program, reaching over 25,000 learners across Kenya, Tanzania, and Nepal. The first phase was implemented in 2022 and 2023 across all three countries, while the second phase was carried out in 2024 in Tanzania and Nepal. Although the program’s core principles remain consistent across countries, its on-the-ground implementation varies based on the partner organization’s approach—particularly in village selection, and the structure and duration of the learning camps and other program components.

This report presents an analysis of children’s foundational learning skills at the baseline for the second phase of My Village in Tanzania and Nepal. The findings are presented jointly, not as a comparative analysis, but to understand learning levels across varied contexts. As part of the baseline assessment, over 8,000 children from 15 villages in Nepal and 20 villages in a remote district of Tanzania were evaluated on their numeracy and reading skills.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the target populations in Tanzania and Nepal differ significantly. In terms of gender distribution, Tanzania has a slightly higher proportion of girls (54%) compared to Nepal (51%).

The age composition of the samples also varies. In Tanzania, the study population is skewed toward younger children: 47% are aged 6–9, while only 8% fall in the 14–17 age group. In contrast, Nepal’s sample is more evenly distributed, with 43% aged 6–9, 34% aged 10–13, and 23% aged 14–17.

School enrollment is high in both countries, with 86% of children enrolled in Tanzania and 84% in Nepal. However, the proportion of children who have never attended school is notably higher in Tanzania (13%) compared to Nepal (5%). Another point of distinction is the type of school attended: 99% of enrolled children in Tanzania attend government schools, while in Nepal, this figure is 65%.

Parental education levels also show marked differences. In Nepal, 65% of mothers have never attended school, compared to only 5% in Tanzania. Overall, 77% of parents in Tanzania (both mothers and fathers) have completed primary education, whereas in Nepal, this figure is just 13%.

The baseline and endline assessments utilized PAL Network’s standardized tools: the International Common Assessment of Numeracy (ICAN) for numeracy and the International Common Assessment of Reading (ICAR) for language and literacy. These adaptive assessments are designed to adjust to each child’s skill level—progressing to more advanced sections only if the child correctly answers the initial, simpler items; otherwise, the assessment concludes at that point.

The ICAN tool evaluates numeracy through tasks focused on number sense, number recognition, and basic operations. The ICAR tool assesses literacy through letter recognition, word reading, paragraph and story reading, and comprehension.

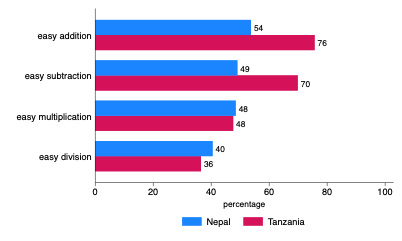

Figure 1: Numeracy performance on easy operations, by country

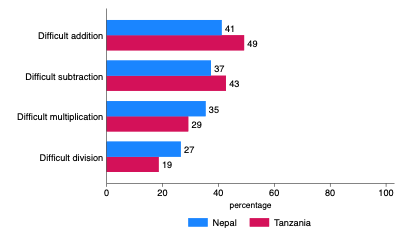

Figure 2: Numeracy performance on difficult operations, by country

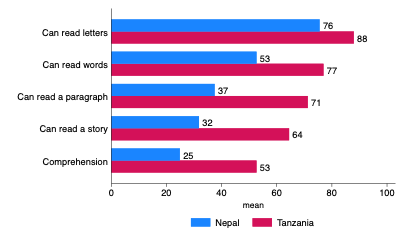

Figure 3: Literacy performance, by country

Note: This graphs represent the percentage of children who answered the difficult operations questions correctly in each country. Number of children, Nepal = 3057, Tanzania = 4105

Overall, children in Tanzania demonstrated higher levels of proficiency in both numeracy and literacy compared to their counterparts in Nepal. In foundational numeracy skills such as number sense and number recognition, performance was relatively strong in both contexts. Recognition of single-digit numbers was nearly universal in Tanzania (96%) and also high in Nepal (84%). However, proficiency declined for double-digit number recognition, with 78% of children in Tanzania and 66% in Nepal able to accurately identify double-digit numbers. Performance disparities became more pronounced in basic operations. In Tanzania, 76% of children were able to correctly solve simple addition problems, compared to 54% in Nepal. This gap narrowed for more complex operations. For instance, in basic division tasks, 40% of children in Tanzania and 36% in Nepal demonstrated proficiency.

In literacy, the performance gaps between the two countries are more pronounced in the more advanced sections of the assessment. While 77% of children in Tanzania demonstrated proficiency in word recognition, the corresponding figure for Nepal was notably lower at 53%. This disparity widens further in long passage reading, where 64% of Tanzanian children were proficient compared to only 32% of children in Nepal—indicating that Tanzanian children were twice as likely to succeed in this more demanding task.

Existing literature highlights that learning outcomes are influenced by a range of factors operating at the individual, household, and school levels. These include gender (Evans & Yuan, 2019), type of schooling (Crawfurd & Hares, 2021), household economic status (Cooper & Stewart, 2020), parental education and involvement in the child’s learning (LeFevre & Sénéchal, 2002), and the language of instruction (Banerjee et al., 2016; Brock-Utne, 2007).

To examine the association between these factors and children’s learning outcomes, item response theory (IRT) modeling was employed for numeracy, while an ordinal logistic regression model was applied for literacy. In the numeracy model, the dependent variable is a standardized score representing latent ability. For literacy, the outcome variable is an ordinal categorical scale, ranging from 1 (letter recognition) to 5 (comprehension), derived directly from assessment responses.

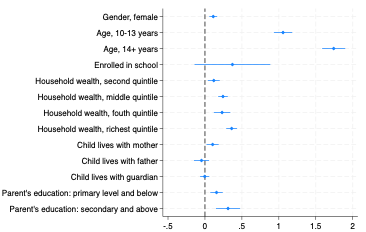

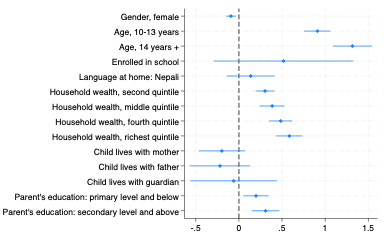

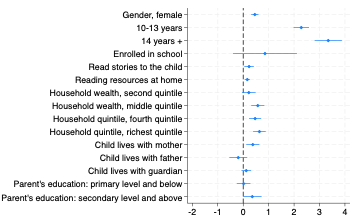

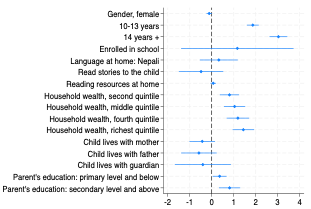

The regression analysis reveals notable variations in predictors of learning outcomes across subjects and contexts. Gender emerges as a significant factor influencing both numeracy and literacy, but with contrasting effects in Nepal and Tanzania. In Nepal, girls exhibit a numeracy ability level that is 0.093 standard deviations lower than boys, whereas in Tanzania, girls outperform boys with a 0.112 standard deviation higher ability level. Similarly, in literacy, being female decreases the odds of higher performance by 11% in Nepal but increases the odds by 59% in Tanzania. Regarding school enrollment, a positive association with ability and performance is observed; however, this relationship is not statistically significant in either context. Household economic status demonstrates a more consistent and pronounced effect: children from wealthier households generally achieve higher learning outcomes compared to those from the poorest quintiles. This effect intensifies progressively across ascending wealth quintiles. Nonetheless, the relationship between household income and learning outcomes appears to be non-linear, particularly in Tanzania. For example, in numeracy, children in the third income quintile exhibit a 0.245 standard deviation increase in ability level, whereas those in the fourth quintile show a slightly lower increase of 0.229 standard deviations.

Figure 4: Coefficient plot, Numeracy, Tanzania (Number of children = 3057)

Figure 5: Coefficient plot, Numeracy, Nepal (Number of children = 4105)

Extensive development literature underscores the positive association between maternal engagement and education and improved health and educational outcomes for children and families (LeFevre & Sénéchal, 2002). Consistent with this evidence, the analysis reveals a significant and positive relationship between a child living with their mother—as opposed to both parents—and learning outcomes in Tanzania for both numeracy and literacy. This relationship, however, is not statistically significant in Nepal. Specifically, in Tanzania, residing with the mother alone is associated with a 0.108 standard deviation increase in numeracy ability and a 47% increase in the odds of higher literacy performance compared to living with both parents.

For children living with both parents, maternal education is used as the proxy for parental education level. A strong positive correlation emerges between parental education attainment and numeracy performance in both contexts. In Tanzania, children whose parents have attained primary education or higher demonstrate numeracy ability levels 0.159 standard deviations above those with parents who have no formal schooling; this effect is even more pronounced in Nepal, with a 0.198 standard deviation increase. The influence of parental education on literacy outcomes diverges between the two countries: in Nepal, primary-level parental education increases the odds of higher literacy performance by 43%, whereas in Tanzania, this relationship is statistically insignificant.

Figure 6: Coefficient plot, Literacy, Tanzania (Number of children = 3057)

For the literacy analysis, additional household factors were incorporated, including whether someone reads stories to the child and the availability of books at home. The presence of story-reading at home exhibited a positive and statistically significant association with literacy outcomes exclusively in Tanzania, where the odds of higher literacy performance increased by 26%. In contrast, this relationship was not statistically significant in Nepal. To measure the availability of books at home, a composite index was created using principal component analysis (PCA). Consistent with the previous finding, a positive and significant relationship between book availability and literacy performance was observed in Tanzania, with the odds of higher performance increasing by 17%. In Nepal, while the association remained positive, it did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 7: Coefficient plot, Literacy, Nepal (Number of children = 4105)

Discussion

This study’s baseline findings from the My Village 2 program provide critical insights into the state of foundational learning outcomes in Tanzania and Nepal, revealing important variations shaped by socio-demographic, economic, and contextual factors. While progress in foundational learning has been made globally, these findings underscore the persistent and uneven nature of educational attainment within and across low- and middle-income countries.

The comparative analysis of numeracy and literacy proficiency highlights both common challenges and context-specific dynamics. In Tanzania, proficiency in basic numeracy concepts such as number recognition and simple operations is relatively high; however, there is a marked drop in performance as children encounter more complex operations such as multiplication and division. This “bottleneck” effect suggests the need for targeted instructional support and pedagogical innovations to help children transition from basic to advanced numeracy skills. Nepal, by contrast, exhibits a more gradual decline in numeracy proficiency, signaling different learning trajectories that may be influenced by variations in curriculum, teaching quality, or learner support mechanisms.

Literacy outcomes reveal even greater disparities between the two contexts. The strong alignment of language of instruction with the child’s home language in Tanzania (where 99% of children speak Swahili at home) likely facilitates learning, compared to Nepal, where only 70% of children speak Nepali at home. This finding echoes a substantial body of evidence supporting mother-tongue instruction as a key factor in improving literacy and broader cognitive development (World Bank, 2021). The lower literacy proficiency observed in Nepal calls for strengthened policies and practices around language inclusivity and tailored literacy interventions.

The gendered dimension of learning outcomes presents a complex and context-specific picture. The finding that girls outperform boys in both numeracy and literacy in Tanzania contradicts common trends observed in many developing countries and invites further investigation. Potential explanatory factors could include Tanzania’s government policies promoting free and inclusive basic education, higher parental education levels, and supportive school and community environments. Conversely, in Nepal, the relatively lower performance of girls aligns with entrenched gender disparities in educational access and learning, underscoring the urgency of gender-responsive educational strategies.

School enrollment status also emerged as a significant factor, with enrolled children in Tanzania performing better than out-of-school children. This finding challenges assumptions about the learning potential of out-of-school children and suggests heterogeneity within this group. While some out-of-school children may be recent dropouts with residual skills, others may lack access to quality learning opportunities. Further qualitative and longitudinal research is necessary to unpack these dynamics and tailor interventions accordingly.

Household wealth remains a robust predictor of foundational learning outcomes, especially in numeracy, consistent with global trends indicating socioeconomic status as a key determinant of educational success (UNICEF, 2022). The influence of wealth likely reflects disparities in access to learning resources, parental support, nutrition, and stimulation, which cumulatively affect children’s cognitive development and school readiness.

Parental education, particularly maternal education, demonstrated a positive correlation with children’s learning outcomes, more strongly in numeracy than literacy. This may reflect cultural perceptions of numeracy as a more practical and immediately applicable skill, but it also highlights the critical role of educated parents in fostering learning at home. The positive impact of maternal engagement, as evidenced in Tanzania, aligns with extensive literature documenting the benefits of parental involvement in children’s educational trajectories (LeFevre & Sénéchal, 2002).

Finally, household literacy environment factors—such as story reading and availability of books—were significantly associated with higher literacy performance in Tanzania but not Nepal. This discrepancy may reflect differences in home literacy cultures, availability of reading materials, or other unmeasured contextual variables, and suggests a potential area for intervention to enhance literacy development through home-based support.

Conclusion

This analysis sheds light on the key factors influencing foundational learning outcomes within the study populations of Tanzania and Nepal. By examining student performance through the lenses of gender, age, school enrollment, household wealth, home language, and various aspects of the home learning environment, the study offers a nuanced understanding of the diverse influences shaping children’s educational experiences. Such insights are essential for designing inclusive, context-sensitive, and effective interventions that address the multifaceted nature of foundational learning.

The findings highlight that foundational education is not a uniform process; rather, it is influenced by an interplay of individual, familial, and socio-economic factors that vary across contexts. This complexity calls for tailored strategies that recognize and respond to these diverse realities rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Moreover, the analysis opens avenues for further research on critical themes such as gender disparities in learning, the impact of school attendance, the role of mother-tongue instruction, and parental education and engagement. These areas warrant deeper exploration to inform more targeted policies and programs aimed at closing learning gaps and fostering equitable educational outcomes. Future publications will delve into these questions with greater detail, continuing to build an evidence base that supports meaningful improvements in foundational learning for all children.

References

- Banerjee et al (2016). Mainstreaming an effective intervention: Evidence from randomized evaluations of “Teaching at the Right Level” in India. NBER working paper No. 22746. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/researchpaper/TaRL_Paper_August2016.pdf

- Brock-Utne, B. (2007). Language of instruction and student performance: New insights from research in Tanzania and South Africa. International Review of Education. Vol. 53, 509-30.

- Cooper K. and Stewart K. (2020). Does household income affect children’s outcomes? A systematic review of evidence. Child Indicators Research. Retrived from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12187-020-09782-0

- Crawfurd L. and Hares S. (2021). The impact of private schools, school chains, and public-private partnerships in development countries. CGD Working Paper 602. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/impact-private-schools-school-chains-and-public-private-partnerships-developing-countries.pdf

- Evans D. and Yuyan F. (2019). What we learn about girls’ education from interventions that do not focus on girls. CGD Working Paper 513. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/what-we-learn-about-girls-education-interventions-do-not-focus-on-girls.pdf

- LeFevre J. and Senechal M. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00417

- World Bank (2022). State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/state-of-global-learning-poverty

- UNICEF (2020). Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/learning-crisis/commitment-action-foundational-learning#commitment