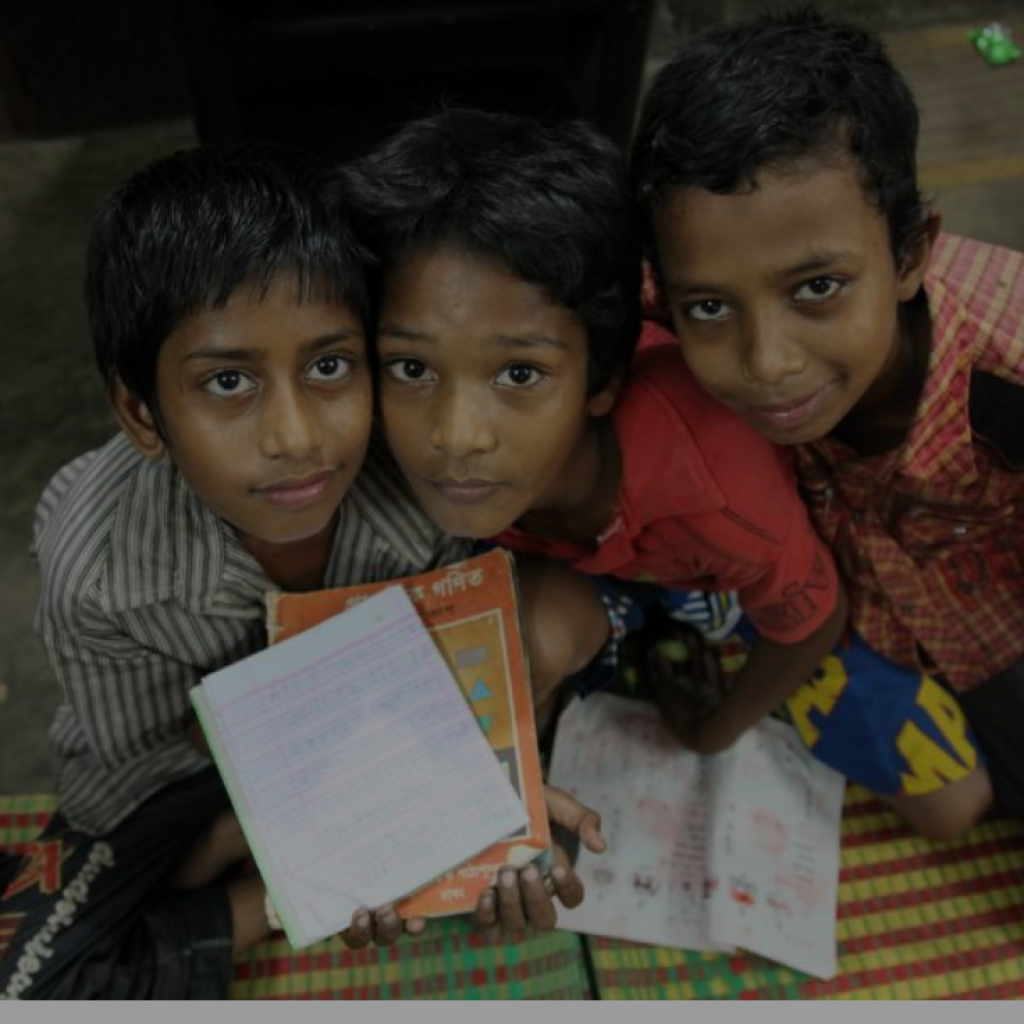

Ambika’s house was built with red bricks and a corrugated steel roof and had spectacularly clear views of the Himalayas. We visited her village to understand whether children went to school and what they were learning. Ambika had two children, Ayush (10) and his little sister Anu (8). They were in Grade 6 and Grade 4. As we sat on Ambika’s porch, parents from neighbouring houses wandered over. We showed Ambika and the other parents the simple numeracy assessment we had brought for the children. One parent, Yam, looked at the test and said, “This test is too simple”. Ambika agreed: “I have seen similar tasks in Anu’s school textbook when she was much younger”. Yam, Ambika, and the other parents were sure their children would be able to do these simple tasks since their children had been going to school for several years.

Introducing ICAN

The simple assessment that we showed Ambika and the other parents is the PAL Network’s new International Common Assessment of Numeracy, “ICAN”. ICAN is an open-source, easy-to-use assessment tool that is currently available in 11 languages. Just like the traditional citizen-led assessments (CLAs) conducted by PAL Network member organisations over the last 15 years, ICAN is administered orally, one-to-one so as to include all children, irrespective of their ability to read. It is carried out in households, and the results, therefore, show learning levels across all children, whether they are in school or not.

ICAN assessment tasks align to UNESCO’s Global Proficiency Framework, offering international comparability of results relevant to Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) Indicator 4.1.1(a), which measures the percentage of children in Grades 2 or 3 who have acquired basic reading and numeracy skills. Whilst Ayush and Anu were taking the ICAN assessment on their porch, the same assessment tool was being administered to more than 20,000 children, in 779 rural communities, across 13 Global South countries as part of ICAN’s first large-scale implementation in late 2019. In each country, one rural district was selected to demonstrate the feasibility of using the same assessment tool across different Global South contexts. The purpose of this first round of household-based implementation was to understand the kinds of comparisons that the use of ICAN can facilitate at scale, rather than to compare assessment results between each sampled location. The ICAN 2019 report presents data from individual districts for a standardised set of indicators.

What does the ICAN 2019 data tell us?

The ICAN results sadly contradict Ambika and Yam’s expectation that schooling automatically translates into learning. Chart 1 (below) shows the proportion of children in Class 2-3 (Chart 1a), Class 4-6 (Chart 1b) and Class 7-8 (Chart 1c) who are able to do a set of foundational numeracy tasks that proxy the minimum proficiency level requirements for SDG 4.1.1 (a). This includes number recognition, simple operations, measurement, spatial orientation, and shape recognition. These charts also identify the class group by when at least three-quarters of children in a given location are able to do the set of tasks (green bars).

For children younger than Ayush and Anu who have already spent between 2 and 3 years in school, less than half are able to do a set of simple numeracy tasks that would be classed as minimum proficiency. Chart 1a shows that in the three best performing locations, little over half the children enrolled in Class 2-3 were able to do the simple numeracy tasks aligned to SDG 4.1.1(a). In the worst-performing location, less than 5% of children in Class 2-3 were able to do the same tasks.

For children like Ayush and Anu who have spent at least 4 years in primary school, Chart 1b shows that even in the 3 best performing locations, approximately one-fifth of children enrolled in Class 4-6 are still unable to do simple numeracy tasks. In the worst-performing location, more than two-thirds of children in Class 4-6 are unable to the same tasks typically expected in Class 2 or 3.

In the 8 locations for which sufficient data is available, it is only by Class 7-8 that all locations except one have over three-quarters of children who demonstrate minimum proficiency. But even in these classes, many children are still unable to do numeracy tasks expected in Class 2 or 3.

Chart 2 explores learning disparities between in-school and out-of-school children taking the ICAN assessment in two locations. In Location 4 and Location 11, over 40% and 30% of children, respectively in the age group of 8-10 years are not enrolled in school. In Location 11, only one-quarter of children aged 8-10 who were enrolled in school, were able to do foundational numeracy tasks. In Location 4, only one in ten children who were enrolled in school were able to do so. In both these locations, this proportion drops to under 3% of out-of-school children taking the assessment. As the 2020 GEM Report underlined in its chapter on data, it is vital that these out-of-school children are included in global data on learning so as to provide a true and inclusive picture of progress towards achieving both national and global goals.

Conclusion

Before the shock created by COVID-19, around 260 million children, adolescents, and youth were already out-of-school. Even among those who were enrolled, large proportions of children were not acquiring even foundational reading and numeracy skills. We know that school closures and other disruptions caused by the pandemic will lead to further learning loss, increased dropouts, and higher inequality. While children are out of school, almost all learning assessments have come to a halt, exacerbating the challenge of obtaining reliable data on learning, particularly for the most marginalised. As the clock ticks to 2030 (the target year to ensure that all children have acquired at least the basics) simple, easy-to-use assessments tools like ICAN provide not only a contextually appropriate way of assessing the foundational skills of all children in both households and schools, but also provide easily understandable data for teachers and facilitators. These help target instruction to the level of each child, in order to make sure that children like Ayush and Anu learn well and are able to fulfil their true potential.

This blog was originally posted in the World Education Blog