The journey to a more equitable and educated world begins with foundational skills. While school enrolment has risen dramatically across the globe in recent decades, a significant crisis persists: many children, despite being in school, are not acquiring basic literacy and numeracy skills. This learning crisis described as ‘learning poverty’[1], traps individuals and communities in cycles of poverty and limits human potential. To truly make a difference, educational interventions must go beyond simply providing access to schooling, and instead focus on what happens inside the classroom. This is the core mission of the People’s Action for Learning (PAL) Network’s My Village project, which aims to bring focused, targeted instruction directly to children in communities one village at a time. The recent impact evaluation of Phase 2, implemented in Tanzania and Nepal in 2024, provides fascinating insights into the program’s effectiveness and, crucially, who it helps the most.

The My Village Intervention Approach

The My Village project incorporated various components to support children’s learning; level-based learning camps, community libraries, Short Message Service (SMS) for parental engagement, and life skills sessions for adolescents. This was aimed at providing a wholistic approach to support children in their learning journey. The second phase of My Village was implemented between July and December 2024, reaching 35 villages across Nepal and Tanzania. In Tanzania, one 30-day cycle was delivered in schools before and after regular hours; in Nepal, two cycles of 60 and 45 days were run in community spaces with daily two-hour sessions.

The My Village project’s core intervention is a series of accelerated learning camps. These camps are a prime example of the targeted instruction approach, a pedagogical approach that has gained significant traction in recent years. Unlike traditional classrooms where all children are taught the same material at the same time, this approach uses a simple yet powerful strategy, borrowing from the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach.

At the beginning of a learning camp, children are assessed to determine their current learning level. They are then grouped with other children who are at a similar proficiency level, allowing facilitators to deliver lessons that meet children precisely where they are, regardless of their age or grade. This personalized, needs-based approach is designed to build upon existing knowledge and close skill gaps efficiently, preventing children from falling further behind. The learning sessions are delivered in a fun and engaging manner, allowing children to learn through play. Perioding assessments are done every 10-15 days to track progress and also inform re-grouping.

A comparative analysis was done between the baseline and endline results, with an effort to measure the program’s impact. This approach allowed us to compare learning outcomes for children who attended the learning camps against those who did not. The evaluation combined propensity score matching and difference-in-difference methodology to address the bias, given that children were not randomly selected to the learning camps. With a substantial sample of over 7,000 children, the evaluation provides a high degree of confidence that the observed changes in learning outcomes can be attributed to the My Village project.

Overall Gains

The overall results from the evaluation were overwhelmingly positive and confirmed the efficacy of the targeted instruction model. Across both countries, the learning camps were associated with significant and substantial gains in foundational skills. The intervention effectively shifted a large proportion of children away from the lowest proficiency levels—defined as not being able to read letters or recognize numbers—and moved them towards mastery. On average, the camps led to a 24-percentage point gain in numeracy and a 25-percentage point gain in literacy across all participants. This indicates a profound improvement in a relatively short period, demonstrating that focused, data-driven teaching can accelerate learning and help children catch up quickly.

Household Wealth and Learning Outcomes

One of the most compelling and nuanced findings from the report is the varying impact of the camps based on a child’s household wealth. The results show that the program’s effectiveness can differ not just between countries, but also among different socio-economic groups within them, highlighting the complexity of educational interventions. The analysis of these heterogeneous effects offers critical lessons for future program design.

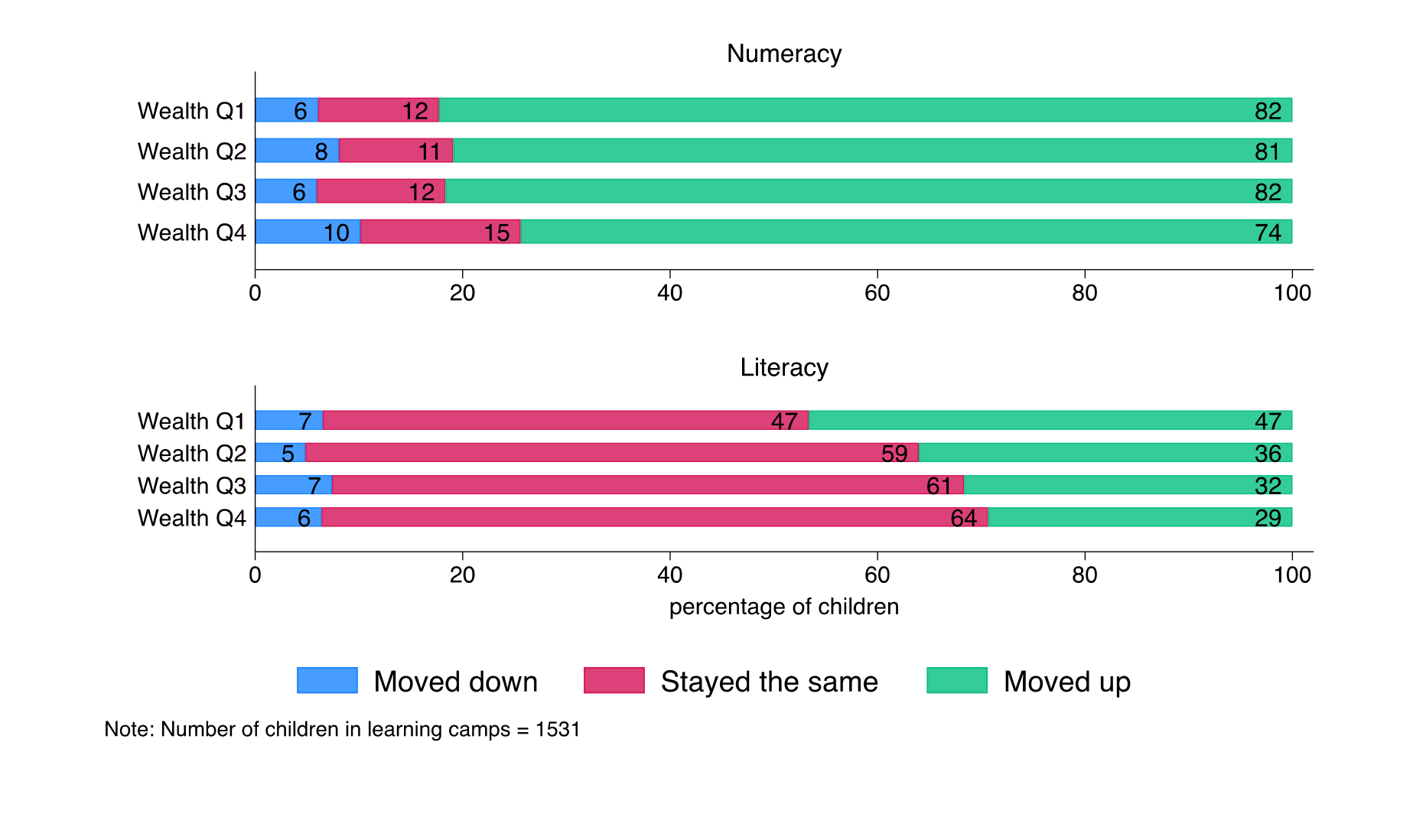

Figure 1: Tanzania: Progress in proficiency among children in learning camps, by household

wealth[2]

In Tanzania, at least 80% of children progressed by at least one proficiency level, with the exception of the wealthiest households, where 74% progressed by at least one level. It is important to note that children from wealthier households were already performing better than those from poorest households at the baseline. In numeracy, children from wealthier households demonstrate significantly higher levels of proficiency compared to children from relatively poorer households. In literacy, 47% of children from poorest households progressed by at least one level compared to 29% from the wealthiest households. For these children, the camps offered an opportunity to receive the kind of focused, remedial support that is often unavailable in schools or in under-resourced homes.

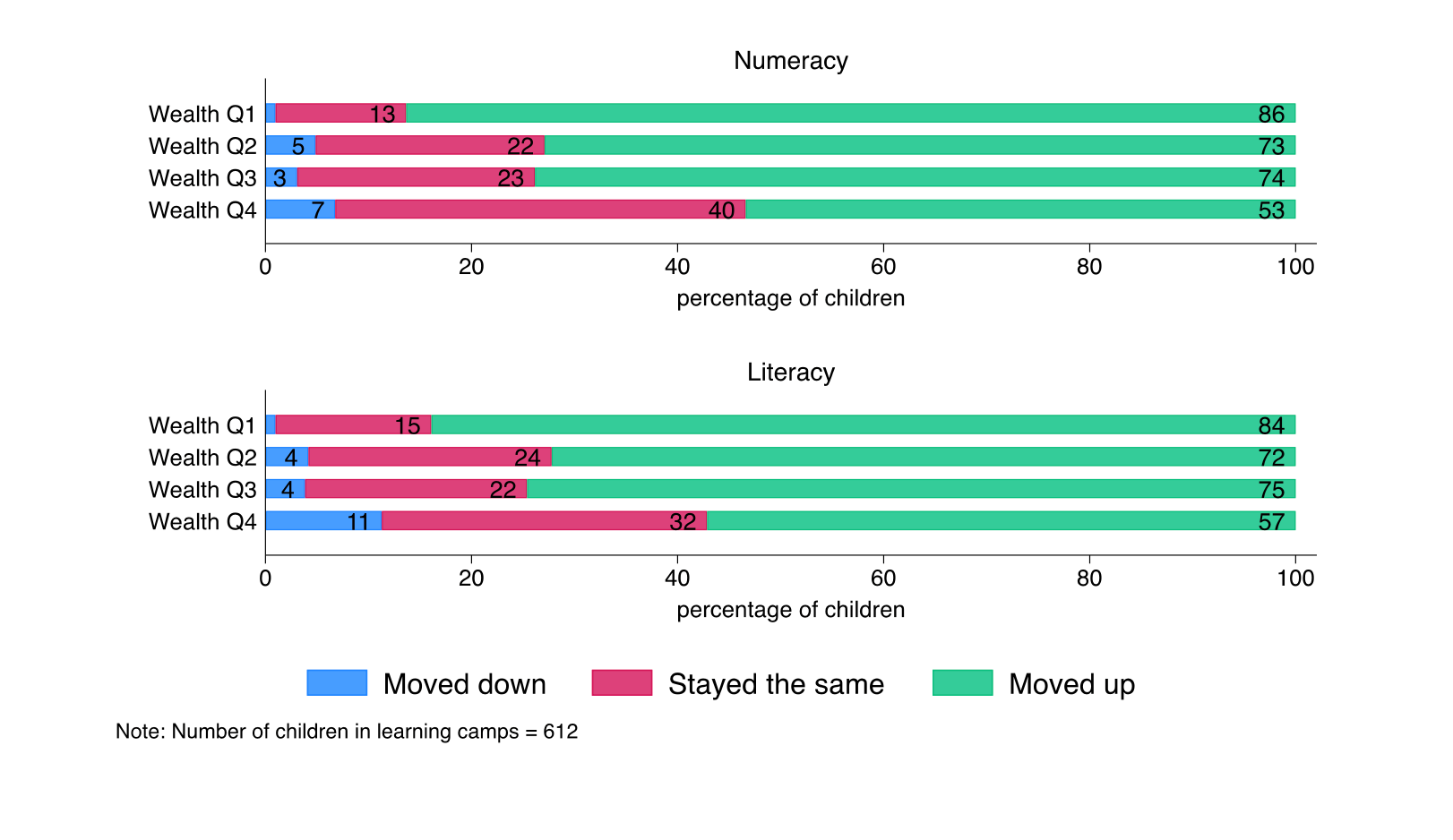

Figure 2: Nepal: Progress in proficiency among children in learning camps, by household

wealth

In Nepal, an equally fascinating trend emerged, where at the onset, a larger share of children from relatively poorer households progressed by at least one level compared to children from wealthier households. In numeracy 86% of children from the poorest households and 53% of the wealthiest households advanced by at least one component level. Literacy had similar results with 84% and 57% for the respective groups. Just as in Tanzania, those who stayed at the same level were already at the higher competencies, for instance, children from the wealthiest households who were already at the most advanced level were 89% in numeracy and 74% in literacy.

Conclusion

The findings across both countries demonstrate a critical truth: a one-size-fits-all approach to education is not enough. Effective programs must be prepared to have a varied impact on different populations. The My Village project has clearly demonstrated what works to support acquisition of foundational skills. The report’s findings confirm that targeted, level-based instruction can lead to significant and substantial learning gains and that it can be adapted to different socio-economic contexts. The analysis on household wealth and learning outcomes offers a key lesson for the future.

We recommend that future iterations of the My Village project explore how to engage better with children from different socio-economic backgrounds and sustain the gains of the children that have acquired the highest competency of reading with comprehension. Continued research into the heterogeneous effects of the different groups of children will also be crucial for refining the model and ensuring that we not only advance learning outcomes but also build a more equitable educational system for all.

[1] Nearly 6 out of 10 children were not acquiring even minimal proficiency in literacy by age 10 before the pandemic hit. And in Sub-Saharan Africa, 86 percent of children already suffered from learning poverty in 2019 (World Bank, 2022)

[2] The quartiles are categorized from Wealth Q1 (poorest) to Wealth Q4 (richest)