Every year, hundreds of thousands of volunteers in South Asia and East Africa walk many miles crossing rivers, mountains, deserts and farmlands to do something amazing: reach remote rural communities to assess whether children can read or do simple maths. Collectively known as Citizen-led Assessments (CLA), every year they show that most children are going to school, but less than half of them can read or write at grade level in countries like India, Pakistan, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. However, in spite of these universally damning reports analysing data collected from nearly a million children in these countries, policy change to improve children’s learning has been painfully slow. So the NGO Pratham that started this movement with the ASER Survey in India is turning its army of volunteer data collectors into change agents to mobilize entire communities and raise awareness about the learning crisis across the whole country.

Over the past decade, citizen led assessment surveys such as ASER in South Asia and Uwezo East Africa have certainly led to new awareness of and widespread discussion about the poor status of learning among the global development community. These assessments, however, have not led to national education system reform to improve the quality of education in these countries (for a humorous take, see how three East African presidents debate this issue here andhere).

So the time has come for an upgrade – creating informed communities to take action on children’s learning. Engaging and mobilizing the community more directly, it is believed, will create the necessary pressure for the system – school administrators, teachers, PTAs, local politicians, etc. – to respond and perform.

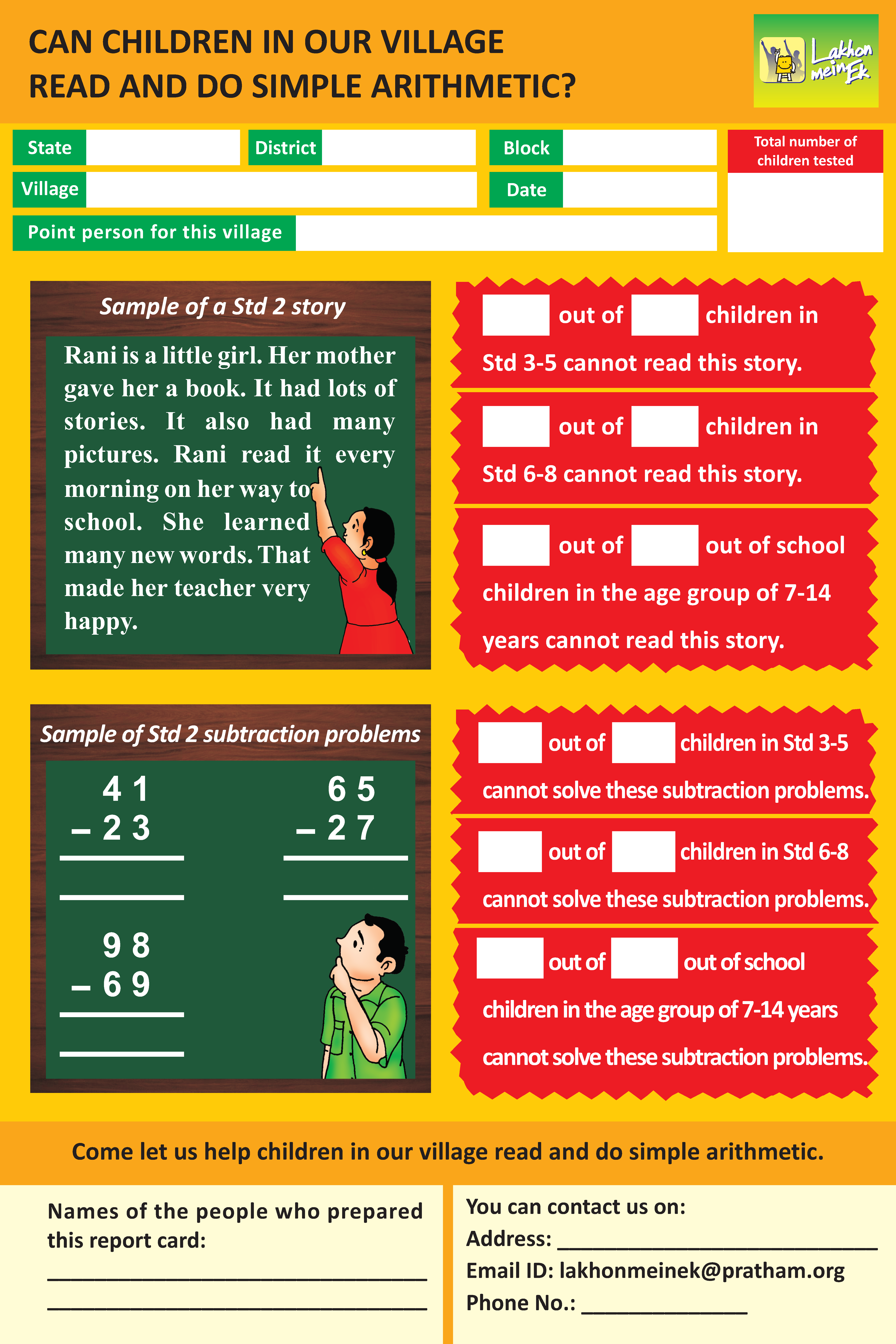

In the course of the last three months, over 330,000 volunteers have mobilized more than 140,000 rural and urban communities in the Lakhon Mein Ek campaign across India. As in previous years, groups of volunteers use a simple language and math tool to test children in the community. However, this year they enter the data on a tablet through the Lakhon Mein Ek application and use a poster to present the data as a report card. With their help, the communities themselves assess their children’s learning, and determine the actions they can take to initiate change.

A recent report by the Results for Development Institutewhich undertook an ‘assessment of citizen-led assessments’ pointed out that the CLAs filled an important void in our understanding of learning outcomes. This is because unlike their counterparts in OECD countries, nationally comparable, methodologically consistent, and regular data on learning outcomes is at best sporadic and at worst, non-existent. However, collecting and disseminating the results of the citizen-led surveys did not seem to galvanize public opinion at a scale that would force the policymakers to put learning as their top priority. On the other hand, evidence from a randomized control trial in northern India has shown that mobilization around the issue of education quality works best when it is complemented by volunteers supporting the teaching and learning process in schools and communities. The new campaign, therefore, aims to bridge the gap between citizen-led assessments and community-led action.

The potential of the massive groundswell of activity in India’s Lakhon mein Ek campaign has to be understood in this broader policy context. It is also interesting that this mobilization has taken place at a time when India is formulating a new education policy. Simultaneously, the focus of the international education and donor community has also shifted to quality, which is one of the targets in the sustainable development goals. In this scenario, empowering citizens through community action will be critical to track, analyse, and build upon as an important piece of the strategy to put learning outcomes at the centre of policy debate in developing countries.

Blog originally posted on the Center for Global Development Website