On one Thursday, during the fifth month of 2019, a school in Ganze, Kilifi County, became our point of interest. We were on an immersion, using the real context of a school to help us understand if the curriculum designs as developed by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development were being interpreted as planned, reflect on the gaps and posit practical solutions. Over 70 people set base in different schools across 18 counties. Our intention was to spend seven school days (which roughly translated to one and a half weeks) in each school. We only managed to reach our school on 5 of these 7 days for when it rains in Ganze, learning comes to a standstill for various reasons.

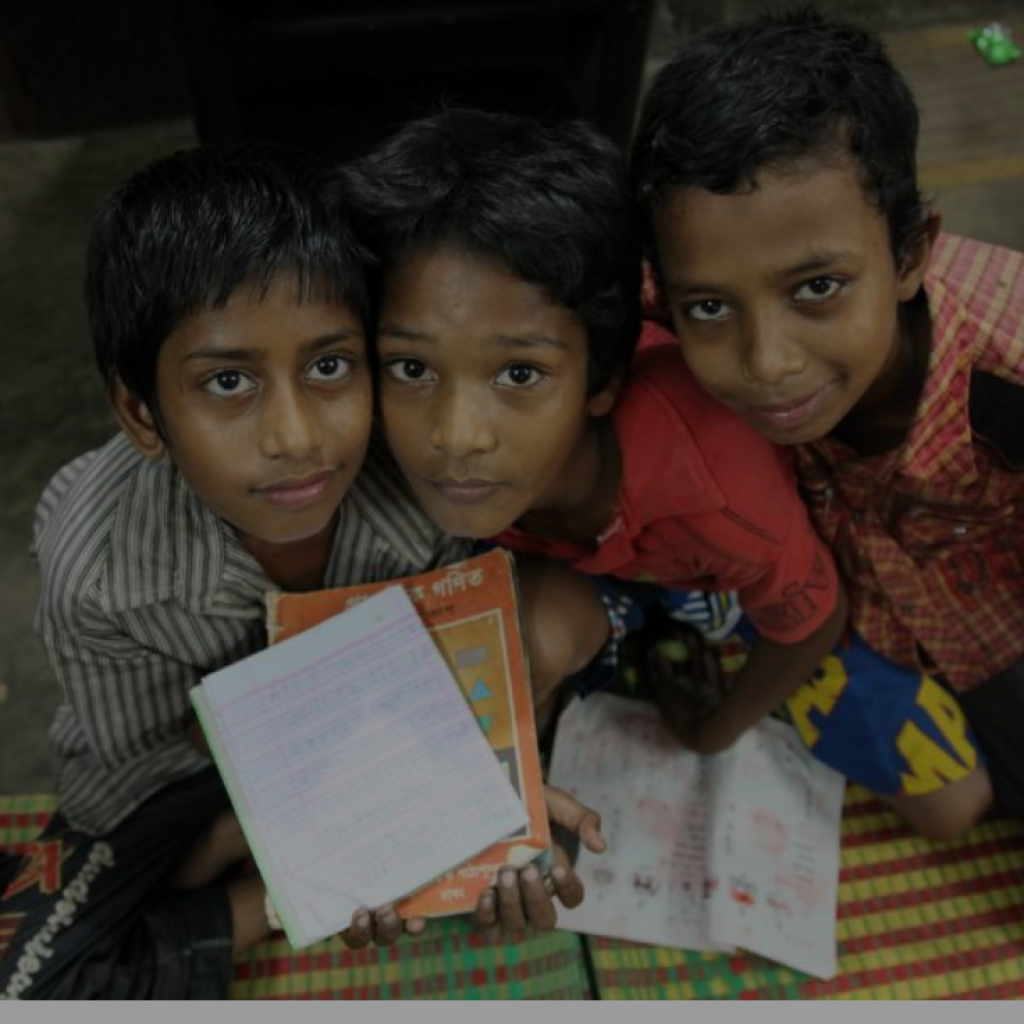

First, when it rains, half of the learners do not come to school. In my assigned Grade 1, attendance on Day 1 stood at 22 children (12 girls) against a normal best of 57 children (24 girls). The official enrolment record is 66 (27 girls). On this day, a light drizzle had persisted for most of the morning. Children from the immediate environs trickled in and accounted for the between 33% to 39% attendance. The fluctuating attendance seems to be the norm, for on Day 7 Friday only 37 children (or 56 to 65%) come to school.

Second, when it rains teachers do not come to school as was the case of the Grade 3 teacher. Others come late. The head teacher arrived in the school at 10.15 a.m. Teacher Rehema, the Grade 1 teacher made her appearance at 11.00 a.m. When I enquired why she was late, her response was ‘niliogapa kuteleza’ loosely translated as “I was afraid to slip and fall”. A valid response. Her mode of transport is a motorcycle. Her school is surrounded by rivers/streams on all sides. There is a steep climb as one approaches the school. When it rains, it gets slippery. Teacher Rehema is heavy with child, and it is therefore very sensible that she takes all precautions to ensure her safety. The bad roads in Ganze know no friend or foe. One Day 2 and Day 4, we were victims of the muddy roads. Stuck. Unable to move. In desperate attempts, shovels were used to scoop out the excess mud in a bid to ‘unstuck’ the lorries and Toyota Probox strewn all over blocking the road. But it was all in vain and this yielded our attendance rate of 71%. This is the context of the school we visited of erratic attendance, and failed infrastructure (be it roads or electricity). It is important to retain the picture of this context.

Yet even in this school there are two scenarios. In Scenario One is the Grade 3 teacher. Let us call him Daudi. He retires in one month. In conversations, the head teacher explains that Daudi is ‘often ill’, ‘is tired’ and irregularly reports to work. This creates a problem. Our intention was to observe and shadow the teacher on Day 1 and 2, and thereafter from Day 3-7 we would teach, model, team teach and seek to introduce tools and approaches that interpret key concepts in the competency based curriculum. With an absent teacher, our plan is dead on arrival. In desperation, the Head Teacher reassigns the Grade 4 Teacher to Grade 3 and this teacher immediately gets to work. When Daudi finally emerges in the school on Day 3, he is relieved, and happily sits in the staff room as he waits for the Grade 4 teacher to ‘officially’ hand over to him so that he can commence teaching. The other teacher, on the other hand, quickly takes over responsibility in Grade 3. During this period, Daudi is in school but not in the classroom where his learners while away the day. One cannot expect learning to happen in the face of an unprofessional and unaccountable teacher personified by Daudi.

Scenario 2: Teacher Rehema, the Grade 1 teacher. She is in school on each day, and on time too, other than on Day 1 when the rains interfered with her. A tall young woman, with a commanding voice and brutal honesty, she is trying to make do with what she has. Rehema is well trained, and has benefitted from 3 Tusome trainings. She has mastered the concepts and knows the drill well ‘thumps up if you can hear the sound, down if you cannot…’ she teaches along. You will not fault her effort. Teach she does. At one point, trying to keep up with the 57 little learners in her classroom, small drops of sweat collect on her nose. She teaches, marks books, managers her class with determination. Often she is unable to do all this in the assigned 30 minutes’ lesson, so her lessons go for one hour. The school has not provided her with manilla papers so she has used her money to purchase some, and has developed some learning aids. Such is the intensity of her effort. Her commitment to her children, and indeed to her profession cannot be questioned.

Yet, however hard she will try, it is highly unlikely that she will succeed in ensuring that all her children learn. She will continue to fall in the folly of teaching the 20-30% who are within the curriculum expectations.

With this, the mission of the Competency Based Curriculum (CBC), of nurturing each child’s potential will come to naught. A new approach is needed.

After two days of observing Teacher Rehema, it is clear that there is a problem, and we need to get a solution. I ask her if she would like to try something new and this is the approach we take before proceeding with the Kiswahili lesson as timetabled:

Step 1: Find out where the child is. We adapt the Uwezo Kiswahili assessment, and assess each child to understand their reading and comprehension levels. Using this simple test we are able to find out that 12 children are at the beginner level – they cannot even recognize a letter/sound. 20 Children are at sound level, 15 at syllable level and 6 at word level. While none can read a short four sentence paragraph we had two children who could read a short story of about 80 words and comprehend it. They were clear outliers. Typically, at this time of the year in Grade 1, one would expect children to be able to read at least words. This is not the case for the majority. For the first time, Rehema knows the reading levels of the 57 children in her classroom.

Step 2: Use the data gathered to make decisions at the classroom level. We use this information to organize learning. First, we rearrange the class into six groups, each having a maximum of 12 children. Then, children are placed according to their levels to allow differentiated tasks.

Step 3: Keep focus on the objective of the lesson, ensuring that you move from listening attentively, speaking, doing, reading and writing.

Step 4: Organise learning to start from whole class activities, then group work and lastly individual work. Through this, we can easily interweave inculcation of values or skilling of competencies within the art of learning.

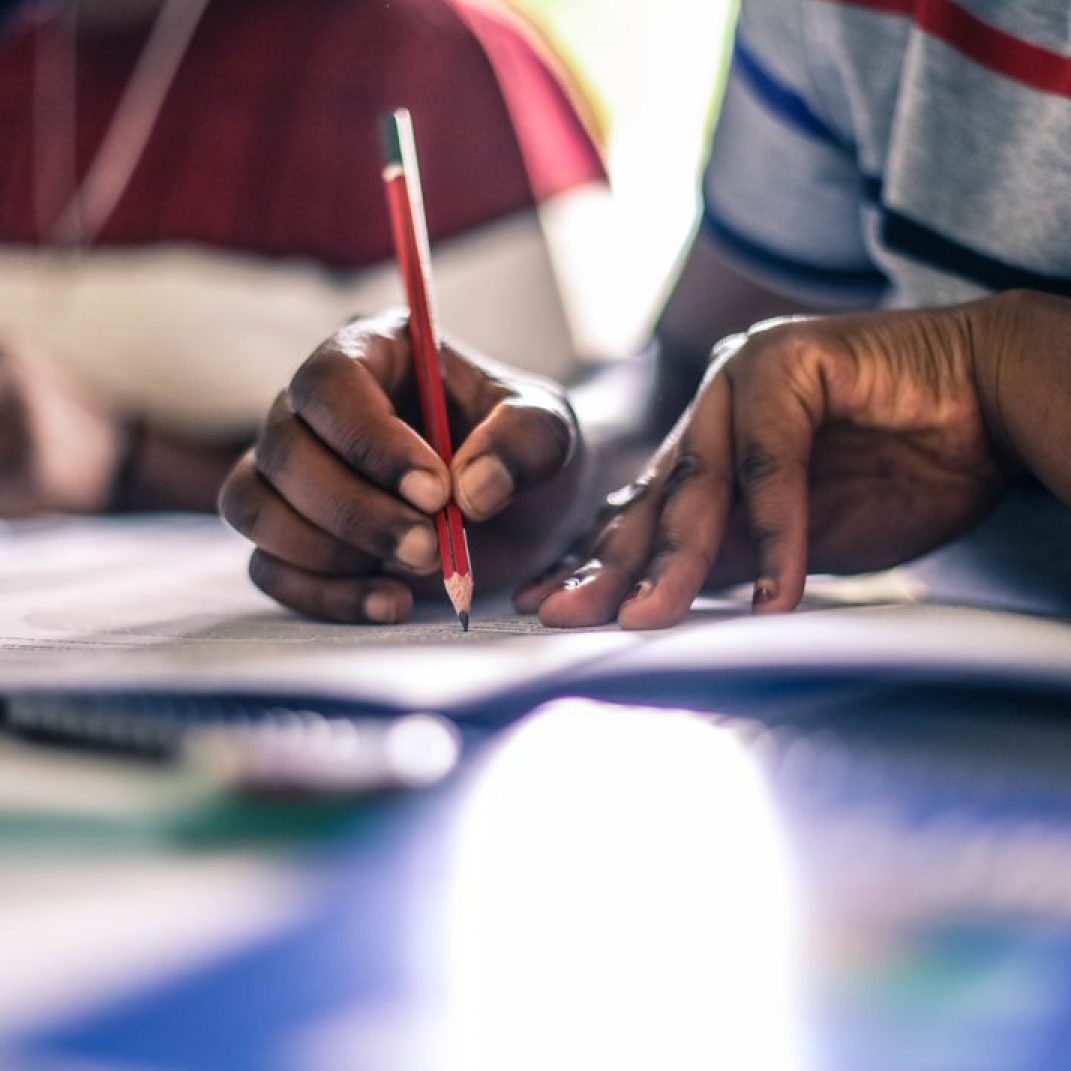

Using these steps, we hold our first lesson. It is the first time most of these little first graders have been asked to work in groups. They do not want to share the few resources. So sharing becomes the value we seek to instill for the week. We use catch phrasing like ‘sharing is caring’. While the text book remains a key resource, we vary the teaching learning process. The ‘mind-map’ is introduced to draw learners experiences as they deliberate on the given sounds /d/ …so rather than tell learners words with the /d/ sound, we ask them to suggest the words starting with /d/. Through this simple activity, we shift from a focus on listening to thinking. Through group work, we start the shift away from the teacher to peer learning. We encourage the children to work with each other, to check each other’s work. Teacher Rehema now walks, gracefully from one group to another, supporting them. Each group has level based tasks…children who cannot read or write sounds are at the tracing level, while the readers are manipulating sentences. Each child is busy doing something. Each child is engaged. It is a frenzy of activity, yet it is in this organized chaos that I see Teacher Rehema smile. She agrees that while she needs more planning, it is actually easier to facilitate learning, rather than to teach. I leave the school confident that Teacher Rehema now has the tools that will allow her to excel in her profession.

The majority of teachers we have in Kenya are trained. They benefit from periodic ‘capacity building’ which needs to go a notch higher. I am persuaded that we now need to change gear from telling teachers what to do, to showing them how to do. We need to change from training to retooling teachers, and through this simple approach, we can collectively create the new teacher with mindset needed in the 21st century. The teacher who is a facilitator of learning rather than just the deliverer of content.