The use and command of the English language is frequently regarded as an indication of upward social and economic mobility. English Medium Instruction (i.e., using English to teach academic subjects) is a highly contested language policy position in multilingual context, often with multifaceted political, socio-cultural and economic implications. While some parents, teachers and policy makers advocate for the use of English as a medium of instruction in schools, researchers and pedagogic theorists argue that prolonged mother-tongue education matters for learning and knowledge attainment

Over the past two decades, the body of evidence on language of education has favoured mother tongue education over English Medium Instruction (EMI) in the early schooling years. Mother-tongue instruction has been shown to lead to cognitive development[i], positive educational outcomes[ii] and downstream human capital formation[iii]. Yet not all the studies have been overwhelmingly positive as some studies have found that among early grade primary school students, mother tongue instruction (MTI) does not have any additional effects on students’ literacy, with students performing worse in their mathematics outcomes compared to non-mother tongue students.[iv] Even where there were some positive effects, these effects diminished by year three leaving indistinguishable differences between mother tongue learners and non-mother tongue learners[v].

In the African context, language of education policies tends to mirror national language policies[vi]; trending towards an early transition from mother tongue education to EMI in lower primary grades. What are the effects of 7-8 years of mother tongue education on students’ mathematics and English achievements? Are they always positive? The question this research asks is whether there is any value-added by introducing English as a medium of instruction in primary schools?

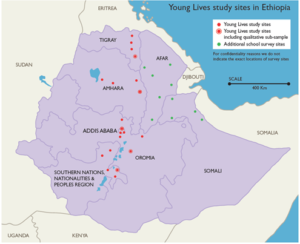

This study uses a longitudinal dataset from Ethiopia, leveraging a variation between a regional language education policy reform for causal identification. Data is collected from Grade 7 and 8 students in five regions in Ethiopia. A value-added model (VAM) of achievement is used in the empirical analysis. VAMs are commonly used in the economics of [i] and the intuition behind this model is to include a baseline achievement measure (a proxy for capturing past unobserved inputs and endowed mental capacity) in estimating knowledge production[i]. The VAM specification used in this study also includes background variables on student and family level characteristics, subject teacher variables and school quality variables.

This study uses a longitudinal dataset from Ethiopia, leveraging a variation between a regional language education policy reform for causal identification. Data is collected from Grade 7 and 8 students in five regions in Ethiopia. A value-added model (VAM) of achievement is used in the empirical analysis. VAMs are commonly used in the economics of [i] and the intuition behind this model is to include a baseline achievement measure (a proxy for capturing past unobserved inputs and endowed mental capacity) in estimating knowledge production[i]. The VAM specification used in this study also includes background variables on student and family level characteristics, subject teacher variables and school quality variables.

The study found that teaching students using English as a medium of instruction compared to teaching them in their mother-tongue reduces their mathematics test scores by 0.2 standard deviations among Grade 7 and 8 students. This is above the median effect of 0.1 standard deviations found in international education studies in low and middle income countries. On English outcomes, the study finds that EMI does not lead to any meaningful improvement when compared to mother-tongue education.

However, the grade at which learners transition to English medium instruction reveals nuanced results. Early grade EMI transitions lead to significantly positive effects in English with null results in Mathematics. Essentially, early transitions positively impact English outcomes with no negative effects on mathematics outcomes, whereas later transitions have negative effects on mathematics outcomes with no effect on English outcomes. This suggests that moving into English medium instruction earlier could reduce the inevitable cognitive demand of learning more challenging content in a less familiar language (i.e., English) in the later school years. These results make the dominant narrative on mother tongue education and positive learning outcomes less clear. It is also noteworthy that even where there is a willingness to implement MTI policies, the instructional environment and implementation challenges encountered may be substantial[i].

In addition, treatment heterogeneity shows no significant differences between girls and boys in EMI and MTI schools. There are also no significant differences between teachers exposed to a national English language improvement programme or due to the years of teaching experience between teachers in EMI and MTI schools.

Nonetheless, in line with pedagogic theorists[ii] and UNESCO recommendations[iii] on language of instruction, it may be prudent for policy makers to consider the tradeoffs, complexity in application, in line with national strategies. In view of this study, when it comes to language of instruction in schools, an early grade EMI transition or sustained mother tongue instruction at the primary school level are policies worth exploring.

[1] Cummins, J., 2000. Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Vol. 23. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.Benson, C., 2000. The primary bilingual education experiment in Mozambique: 1993 to 1997. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 3, 149–166.

[1] Vujcich, D., 2013. Policy and Practice on Language of Instruction in Ethiopian Schools. Young Lives.Eriksson, K., 2014. Does the language of instruction in primary school affect later labour market outcomes? Evidence from South Africa. Economic History of Developing Regions 29:2, pages 311-335.

Seid, Y., 2016. Does learning in mother tongue matter? Evidence from a natural experiment in Ethiopia. Economics of Education Review, 55,21–38.

Seid, Y., 2019. The impact of learning first in mother tongue: evidence from a natural experiment in Ethiopia. Applied Economics, 51(6), 577–593.

Taylor, S., & von Fintel, M., 2016. Estimating the impact of language of instruction in South African primary schools: A fixed effects approach. Economics of Education Review, 50, 75–89.

[1] Ramachandran, R. 2017. Language Use in Education and Human Capital Formation: Evidence from the Ethiopian Educational Reform. World Development 98: 195–213. [1] Piper, B., Zuilkowski, S. S., Kwayumba, D., & Oyanga, A., 2018. Examining the secondary effects of mother-tongue literacy instruction in Kenya: Impacts on student learning in English, Kiswahili, and mathematics. International Journal of Educational Development, 59(July 2017), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.10.002 [1] Slavin, R. E., Madden, N., Calderón, M., Chamberlain, A., & Hennessy, M., 2011. Reading and language outcomes of a multiyear randomized evaluation of transitional bilingual education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373711398127 [1] Clegg, J., & Simpson, J., 2016. Improving the effectiveness of English as a medium of instruction in sub-Saharan Africa. Comparative Education, 52(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1185268 [1]Andrabi, T., Das, J., Khwaja, A.I., Zajonc, T., 2011. Do value-added estimates add value? Accounting for learning dynamics. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 3 (3), 29–54. [1] Todd, P.E., Wolpin, K.I., 2003. On the specification and estimation of the production function for cognitive achievement. Economic Journal, 113 (485), F3–F33. [1] Iyamu, Ede O.S., Ogiegbaen, Sam E. Aduwa, 2007. Parents and teachers’ perceptions of mother-tongue medium of instruction policy in Nigerian primary schools. Language, Culture and Curriculum. 20 (2), 97–108.Nyaga, Susan, Anthonissen, Christine, 2012. Teaching in linguistically diverse classrooms: difficulties in the implementation of the language-in-education policy in multilingual Kenyan primary school classrooms. Compare: J. Comp. Int. Educ. 42 (6), 863–879. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.707457

[1] Alidou, H., Boly, A., Brock-Utne, B., Diallo, Y. S., Heugh, K., & Wolff, H. E., 2006. Optimizing learning and education in Africa – The language factor. Paris: ADEA. [1] UNESCO. (2016). If you don’t understand, how can you learn? Policy Paper 24.