“What do they do here?” the Uber driver asks, as we exit the National Council of Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD).

I had ordered the ride earlier to deliver a letter of invitation to the Chief Executive Officer of NCPWD, asking that he appoints two representatives to attend a policy dialogue in Kisumu, Kenya within the month.

“They are a state corporation. Their purpose is to promote equal opportunities for people with disabilities. They also provide resources to help them live a decent life.”

I take a breather. He’s looking to join the road, so I wait for him to do so before I proceed.

“Persons with disabilities are also tax-exempt, so if they have an NCPWD number, they can take advantage of that benefit.”

I stopped and waited for him to ask a follow-up question; he appeared to have one. He takes his time.

“Are there any branches in the counties? Can I register someone there?” He asks, after a brief silence.

“They do have offices in each county, and you should be able to register someone,” I replied, but I had a question, so I let it out. “Do you know anybody?”

He takes a deep breath as we make a U-turn on the highway. He’s taking me back to the office.

“My cousin has a disability. She’s an adult now. She is twenty years old.”

“Twenty years old! Why isn’t she registered yet?” I’m immediately surprised, but hold back and allow him to proceed.

“Nobody wants that burden,” he says, referring to his cousin’s inability to walk. He checks his side mirror before turning onto St. Michael’s Road. “My grandmother cannot carry her to the registration offices; they must come to her,” he retorts, somewhat angry. He was getting upset but trying to hide it.

“My uncle is a drunk, he doesn’t care!” He exclaims harshly.

We were planning a policy dialogue on expanding equity and inclusion in the education and employment of people with disabilities. However, it just dawned on me how real and close the issues were. There was a young female adult somewhere who had never attended school, had never gone further than where she was born and barely left the house. She is disabled and must be carried everywhere she goes. She’s being cared for by a grandmother whose kindness has led her to bear this responsibility alone. There is no point in mentioning her father, who drinks himself into the trenches, possibly avoiding the reality of having a disabled child.

“Has she been to school?” I ask calmly, bracing myself for his reaction.

“She has never attended school. She’s an adult, but they treat her like a child!” This time, he speaks with obvious frustration.

“Perhaps my grandmother would not have had to struggle as much if she had been registered.”

“I’ll tell them to take her to the registration office,” he says with finality. He stops at the parking lot’s entrance. I pay him and exit the cab.

This conversation stayed with me. I couldn’t help but think about how many other children have a similar story to this one. Even in today’s world, we still hide behind the notion that a disabled child is a bad omen. We haven’t really learned much, have we?

[/av_textblock]

[av_image src=’https://palnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/DSC03246-1030×685.jpg’ attachment=’24443′ attachment_size=’large’ align=’center’ styling=” hover=” link=” target=” caption=” font_size=” appearance=” overlay_opacity=’0.4′ overlay_color=’#000000′ overlay_text_color=’#ffffff’ animation=’no-animation’ admin_preview_bg=”][/av_image]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=” av-medium-font-size=” av-small-font-size=” av-mini-font-size=” admin_preview_bg=”]

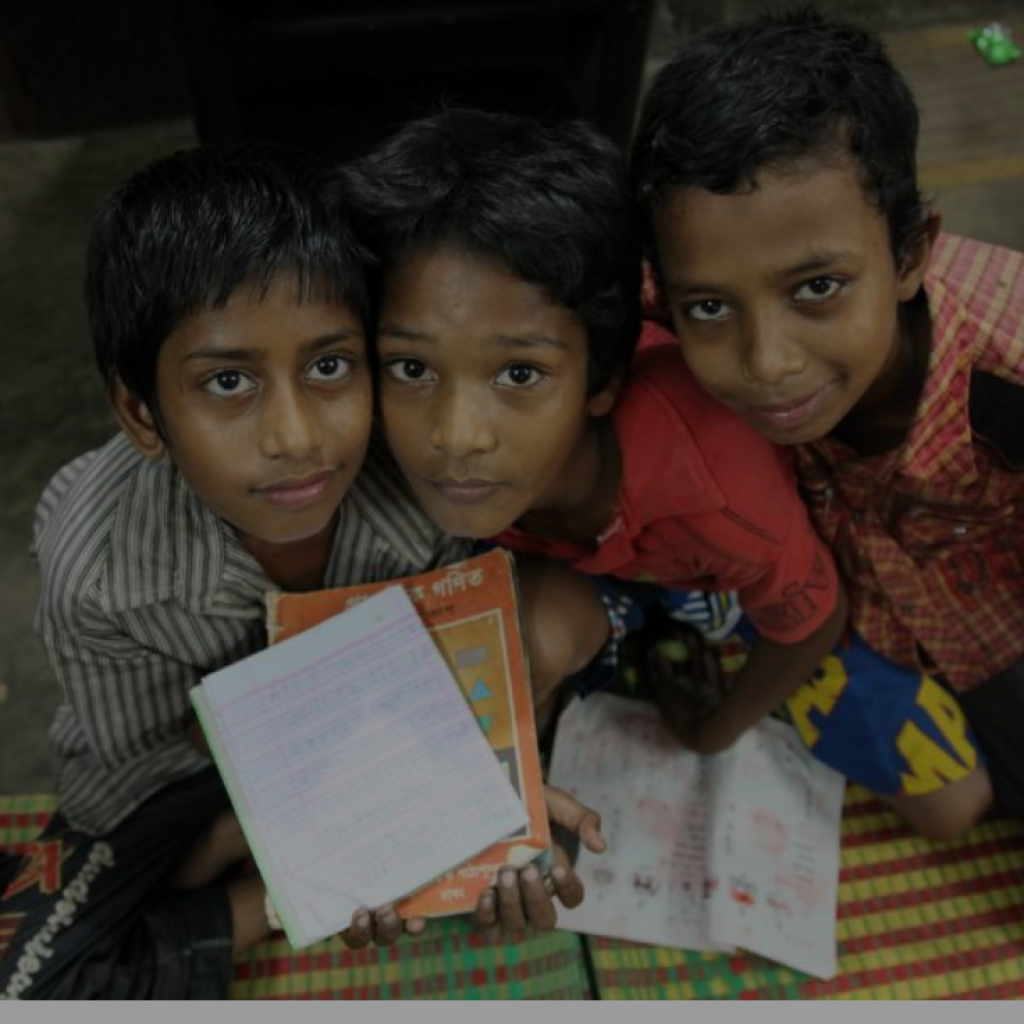

According to the most recent 2019 census, 2.2% of Kenyans aged five and up have special needs or a disability, totalling 918,270 Kenyans (KNBS, 2020). Given the limited range of special needs considered, this is the lowest estimate established by a study on people with disabilities. The Ministry of Education National Survey (2018) reported an 11.4% disability prevalence based on 3-21 years; the Kenya National Census of 2009 reported 3.5%; and the Kenya National Survey for Persons with Disabilities (KISE (Kenya Institute for Special Education) (2006) reported 4.6%. Based on these findings, the population of Kenyans with special needs and disabilities could range between 400,000 and 2.3 million. This is an alarming uncertainty, partly because if the Government doesn’t have a clear number of people with special needs and disabilities, it cannot effectively allocate resources to cater to their needs.

More challenges, particularly affecting children with disabilities, emerged during the policy dialogues we held in Nairobi, Kisumu and Kilifi, Kenya. The discussions focused on a survey conducted by the PAL Network and supported by the Include platform on the inclusion of learners with special needs in education and employment. The report illustrated the barriers to quality education, with inadequate infrastructure grants for special primary and secondary schools being the predominant barrier. This emphasises the need for appropriate equipment for learning to take place in these schools. Without these, it is difficult to teach them the necessary skills.

For the policy dialogues to bear fruit, the Persons with Disabilities (PWD) Act (2003) needs to be revised. It will help harmonise and align it to the Kenyan constitution (2010) and Vision 2030. This would also facilitate its full implementation and compliance with the Convention on the Rights of PWDs. These documents have detailed information on ways governments can support PWDs. The other recommendation is to look into the special needs courses offered in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) institutions. It is important to align these courses to current market trends and invest in technologies that aid PWDs in learning. Finally, utilise lessons from other parts of the world to implement conditional cash transfers to strengthen the existing social protection models.

“Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programmes aim to reduce poverty by making welfare programmes conditional upon the receivers’ actions. That is, the Government only transfers the money to persons who meet set criteria. These criteria may include enrolling children in public schools, getting regular check-ups at health facilities and receiving vaccinations.” Ariel Fiszbein, Norbert R. Schady. 2009. Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty. © World Bank.