Mwibale primary school in Western Kenya is a testimony of what the power of reading can achieve even among the furthest behind communities. On this sunny afternoon, I take a ride to the school to meet the headteacher, who had been looking to meet us for some time. The sight of learners under trees reading aloud initially shocks me. Does the school have no classrooms, forcing these groups of learners to study under the trees? Teachers are walking around, pausing at intervals to engage learners in conversation. At this point, the headteacher catches up with us.

He greets us with a beaming smile and joyfully expresses his gratitude to us for having made it to his school. ‘These are grade 1 to 3 learners participating in their daily read aloud sessions. They come back every afternoon for an hour for this. The Accelerated Learning Programme taught us one thing; if a child can read, then we are assured of a smoother learning process,’ remarks the headteacher. Read aloud sessions are part of the school routine for each grade at Mwibale, usually taking place outside the classroom and supervised by assigned teachers. As a result, the enrolment has doubled, with learners transferring here from nearby private and public schools. Community support is on another level. Whereas in the past, parents would have argued that learners had chores at home, none withholds their child from coming back for the sessions after lunch.

Mwibale represents many public schools that have been struggling with low learning outcomes. The Uwezo report (2015) ranked Bungoma County among the bottom 10 counties on foundational literacy and numeracy outcomes, hence the selection of this county for the ALP intervention. At the time, only 15% of the children assessed in the county could read a grade 2 level text in English. When we assessed Mwibale, 50% of the grade 5 learners could not read a grade 2 level text. Among these children was a girl called Centrine, who could not recognise letters at the time. Today, her performance is above average in all subjects, and she aims to secure high school placement in a county school. Her hope for a brighter future is renewed as she sits her national primary examinations this year.

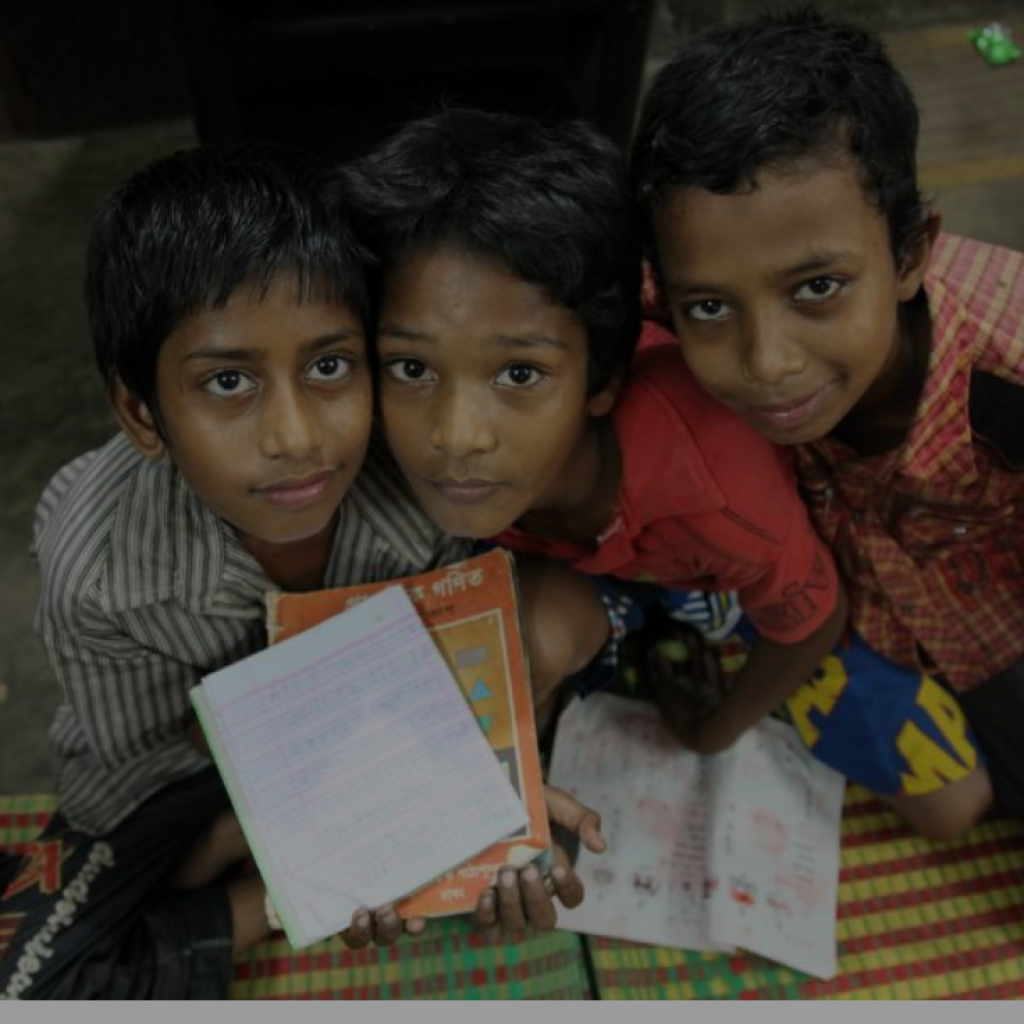

Nothing is as empowering to a child as the ability to read and derive meaning from what they read. However, this is not always the case for many children. A recent study by Usawa Agenda in Kenya established that only 40% of those in grade 4 met the reading expectations of a grade 3 learner. Of those in grade 4, 60% are, therefore, lagging in competencies they should have acquired a year earlier. Out of the girls assessed in grade 4, 57% could not read a grade 3 level text. Besides wealth and the type of school attended (private or public), the report established;

‘Mothers education plays a significant role in improving the learning outcomes of a child. Using children born to mothers with utmost primary education as the reference group, the odds of having better learning outcomes are 50% and 80% higher for pupils born to mothers with secondary and tertiary education.’

The finding serves to emphasise the need to invest in quality education for all, but particularly for mothers as they greatly influence their children’s learning achievement. We look to the mothers in grade 4, who constitute 57% of the girls trailing behind, to support education in the future. Not only are they instrumental in the learning outcomes, but research has also established that households with educated mothers reap better health benefits.

As we commemorate the International Women’s Day and renew our pledge to #Breakthebias, it is critical to reflect on the need to equip learners with the right foundations early on. Foundational literacy and numeracy skills are a prerequisite for the development and acquisition of other competencies (Belafi, C., Hwa, Y., and Kaffenberger, M. 2020). They are the blocks upon which learners build competencies in other subjects, thus enhancing their learning trajectory. Learners who cannot read have difficulty interacting with course material in other subjects. The inadequate literacy skills also hinder their independence in learning and ultimately, reduce their performance, increasing the risks of absenteeism and school dropouts. This is particularly so when learners fail to read at the right age, as they may never catch up, putting their academic pursuits at stake. This limitation jeopardises their career aspirations and limits their contribution to the economic life of their countries.

But what will it take to get us there? Increased funding alone may not suffice, as inputs rarely yield improved learning outcomes for learners who are behind. Investing in teacher capacities to deliver quality education, particularly foundational literacy and numeracy, may be a good starting point. If we have quality preservice and in-service teacher education programmes, our teachers graduate better able to plan for and handle literacy and numeracy instruction during the early years. Regular exposure with children during training helps them to better conceptualise the classroom reality and nurtures an appreciation for the diversity they will encounter daily at work.

Assuring our girls of a quality education today is the shortest route to breaking all educational, economic or social biases.