I used to debate with my former Gates Foundation colleague Manami about the importance of #blacklivesmatter. Essentially, I took the Hilary Clinton stance: without specific policy proposals, it wouldn’t lead to real change. Manami said it would change the rules of the debate, that the media would change their frame from focusing on acts of individual racism to the roots and effects of systemic, structural racism. I think Manami was mostly right and I was mostly wrong. Just look at the overwhelming reception to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ latest book Between the World and Me. Or the way that #blacklivesmatter has permeated popular culture — from social media to D’Angelo’s long-awaited comeback to Beyoncé’s latest super-hit to Macklemore’s spoken word reflections on white privilege. Even someone as fond of cynicism as myself cannot take the societal influence of #blacklivesmatter for granted. We haven’t seen immediate, quantifiable change, but we know that today’s youth are growing up immersed in a very different discussion about race and racism than my generation did just 15–20 years ago.

Ethan Zuckerman from MIT’s Center for Civic Media has been developing an argument that #blacklivesmatter is indicative of a new kind of “insurrectionist civics”:

The #blacklivesmatter movement wants to pass laws, but its leaders also recognize that disproportionate violence against black people isn’t going to be ended just by passing laws or putting cameras on every police officer — it was already illegal for Michael Slager to kill Walter Scott. We need to change the norms of our society so that black men and boys aren’t automatically viewed as potential threats.

We tend to describe the impact of the civil rights movement with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. We describe the success of the gay rights movement with the legalization of gay marriage. But if #blacklivesmatter activists don’t gauge their success in units of new legislation or judicial decisions, then how do they know whether they are making progress or not? Ethan promotes the concept of “monitorial citizenship,” using police monitoring as an example:

“Monitoring” sounds passive, but it’s not — it’s a model for channeling mistrust to hold institutions responsible, whether they’re the institutions we’ve come to mistrust or the new ones we’re building today. When the Black Panthers were founded in Oakland, CA in the late 1960s, they were an organization focused on combatting police brutality. They would follow police patrol cars and when officers got out to make an arrest, the Panthers — armed, openly carrying weapons they were licensed to own — would observe the arrest from a distance, making it clear to officers that they would intervene if they felt the person arresting was being harassed or abused, a practice they called “Policing the Police”.

Monitorial Citizenship is a powerful way of holding institutions responsible that benefits from technology because it allows many people working together to monitor situations that would be hard for any one individual to see.

Monitorial Citizenship to Improve Education

This week I am in Senegal at an inspiring meeting of a grassroots activiststrying to improve basic literacy and numeracy skills in their countries. They are already established in India, Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Senegal, Mali, Mexico, and emerging in Cameroon, Mozambique, Mauritania, Niger, Ghana, and Bangladesh.

Why are they all focused on education? As Homi Kharas explains in the above video, “if you look at development today, there are three massive challenges that everyone is talking about: the first is jobs, the second is better prospects for young people, and third is inequality. And when people ask, how are we going to resolve these three things? Well, the answer is education.”

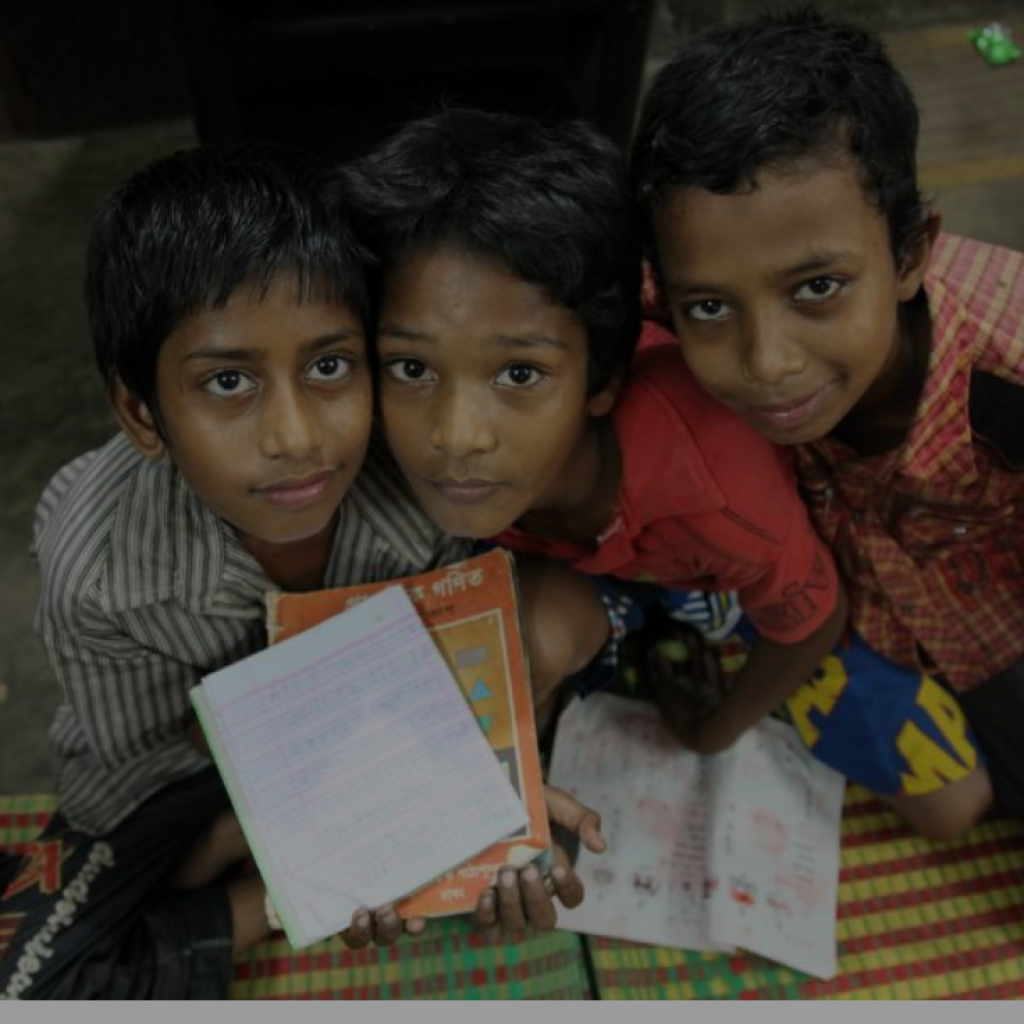

The individuals gathered here in Senegal are the pioneers of a global movement for monitorial citizenship. Together they have mobilized hundreds of thousands of volunteers to fan out across their communities and knock on the doors of homes, huts and apartments to test the literacy and numeracy skills of school-aged children. If you’re interested in the specifics, Tina Rosenberg published a thorough profile in the New York Times in 2014 and Anit Mukherjee penned a more recent overview for the Center for Global Development. In India alone last year, they managed to reach ten million children with a basic survey. Yes, ten million. Researchers use that information to gauge whether or not learning outcomes are improving, and advocates use the results to stress to public officials the importance not just getting more children into school, but also ensuring that they are learning once they are there. As an international coalition of organizations, they worked together to ensure that Sustainable Development Goal #4 wasn’t just focused on the number of children enrolled in school, but also whether or not they are learning.

Changing Laws, Changing Hearts & Minds

Almost from day one, much like the activists of #blacklivesmatter, citizen assessment organizations faced skepticism that citizen monitoring would reform deeply entrenched education systems with politicians on the defensive, poorly paid teachers, missing textbooks and crumbling classrooms. That’s not to say that politicians weren’t paying attention to their work, but there has been little evidence of new education policies as a result that have contributed to significant improvements in learning outcomes.

These massive networks of volunteers don’t just want to change laws, they also want to change the hearts and minds of their fellow citizens by demonstrating that they too are responsible for the education of the young people in their communities, and that they too can make a difference. Of course basic education is the responsible of the governments that represent us. But education is more than what happens in the classroom. We can all do more as parents, mentors, and tutors. We can provide additional support to teachers’ most exciting and innovative projects through platforms like DonorsChoose, or we can try our hand at teaching through programs like Teach for India. We can mentor via organizations like Big Brothers, Big Sisters, or we can tutor some young students in need after work at centers like 826 National. In many developing countries, however, these programs don’t yet exist. In Mexico City, where I had even more privilege than I do in California, I wasn’t able to find a single youth-serving organization where I could volunteer regularly during the five years I lived there.

I expect this will soon change. Mexico is one of the newest countries to join the global network of citizen assessments, and most of their volunteer surveyors are university students. Felipe Hevia, the director of Independent Measurement of Learning (MIA), told me that participating in these neighborhood surveys is a gateway drug that develops a sense of what would be fair to call “insurrectionist civics.” The volunteer surveyors truly understand the dismal state of education in their communities. They develop a sense of responsibility to address the problem, and a sense of empowerment to truly make a difference.

It could very well be that the greatest impact of citizen assessments of learning lies less in the political influence of survey results than the transformation of the volunteer surveyors who participate in the process.

(The photos accompanying this post are from a field visit to Rufisque with the Senegalese citizen assessment organization Jangandoo whose work was profiledby my colleague Pat Scheid last July. Well, most photos — Beyonce didn’t join.)