By Najme Kishani (Research Manager), and Winny Cherotich (Action Manager)

Introduction to the My Village project and the impact

The My Village Project is an initiative by the People’s Action for Learning (PAL) Network aimed at mitigating the learning crisis in Kenya, Tanzania, and Nepal. The first phase of this project addressed the alarming statistic that over half of the 45,000 children assessed in the sampled 304 villages in Nepal, Tanzania, and Kenya had not acquired basic literacy and numeracy skills. The intervention employed a multifaceted approach to enhance children’s foundational learning, including learning camps providing interactive level-based learning regardless of children’s age or grade, community libraries enabling children to access reading materials to cultivate a reading culture and sustain learning gains, thematic messages engaging parents and complementing the face-to-face sessions, and life skills sessions focusing on communication, problem solving and collaboration.

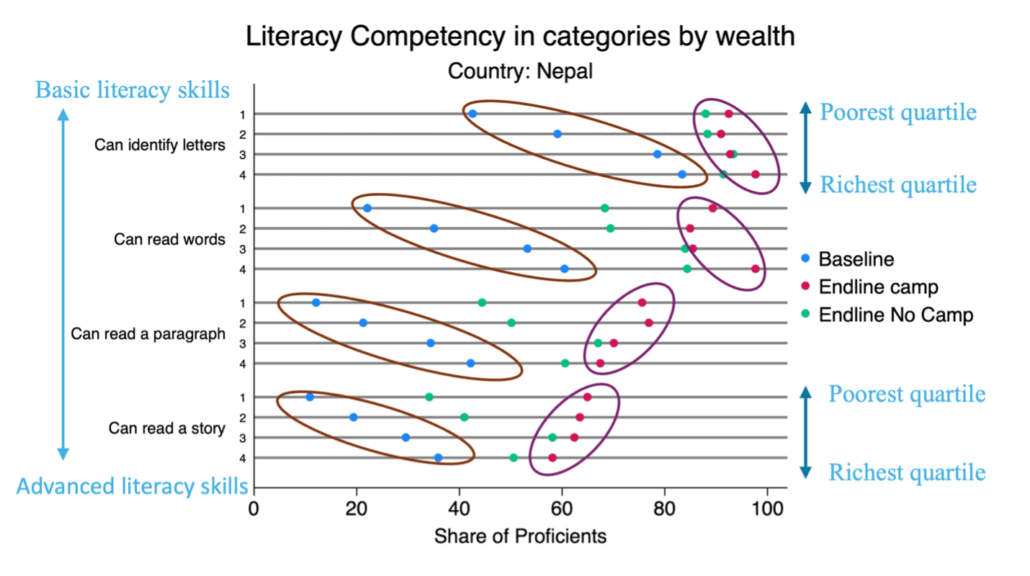

The My Village project significantly improved learning outcomes and narrowed the education gap between children from wealthier and poorer households, based on pre-post comparison. Figure 1, for instance, shows children’s literacy competency across wealth quartiles, from baseline to endline, for both camp participants and non-participants in Nepal, with a sample size of 16,103. At the baseline, children from richer households significantly outperformed those from poorer households across all literacy skills. However, the learning camps helped narrow and even close this gap. The results show that children who attended the learning camps significantly improved their literacy skills, especially those in the poorest quartile. Notably, in the most advanced skill sets—reading paragraphs and stories—children from poorer households even outperformed their wealthier peers by the end of the intervention. While the results suggest a strong positive impact, they are not conclusive and further rigorous testing is needed to confirm which specific programme components work best. The results underscore the effectiveness of localised, equity-focused educational interventions in not only improving foundational skills but also in leveling the educational playing field for marginalised children.

The success of the My Village Project demonstrates that even small adjustments to educational programmes can lead to significant improvements in learning outcomes. However, to maximise the effectiveness of these interventions, it is essential to rigorously assess which components work best. By evaluating and refining specific programme elements—such as teaching methods, parental involvement, and learning materials—through targeted testing, we can ensure that every initiative delivers optimal results for children’s foundational learning. This is where A/B testing becomes a powerful tool for enhancing impact.

Figure 1: Literacy Competency in Nepal, by Wealth Quartile

What is A/B testing? Why and how we are using it

A/B testing is a controlled experiment used to compare two versions of a programme to determine which performs better. In educational interventions, such as the My Village project, this method allows testing specific interventions—such as different teaching techniques or engagement strategies—by randomly assigning participants to two groups and analysing the outcomes. A/B testing provides data-driven insights, helping identify the approaches that lead to significant improvements in learning outcomes, making it an essential tool for scaling effective, evidence-based education solutions. Moreover, A/B testing is considered a cost-effective approach because it allows organisations to focus on small-scale, targeted testing, minimising the risk of investing resources into less effective strategies. By making data-driven decisions through A/B testing, resources can be optimised, leading to better outcomes without unnecessary expenditures.

Preparation for A/B testing

PAL Network has embarked on employing A/B testing to enhance the effectiveness of the My Village project across Kenya, Nepal, and Tanzania. In preparation for a full-scale A/B testing process, PAL Network, in collaboration with its Botswana-based member, Youth Impact, conducted a pre-pilot phase to test specific adjustments and ensure feasibility for larger-scale testing. The process began with an inception meeting in May 2023, where stakeholders aligned on the research objectives and priorities. Over a series of sessions, each country identified specific adjustments to test for their potential impact on improving children’s foundational learning. The Nepal team chose to explore the role of parental involvement in boosting learning outcomes, while the Tanzania team focused on whether increased headteacher engagement could enhance the overall effectiveness of the learning camps.

The A/B testing pre-pilot phase was conducted over six to eight weeks, comparing programme tweaks in Group A with a control group in Group B. Baseline and endline assessments were critical in providing insights into the effectiveness of these interventions. During this phase, teams familiarised themselves with the A/B testing approach and ran a small pilot to ensure a smooth roll-out in the next phase. In Nepal, the sample included 150 children, 75 in each group. Complete randomisation was not possible since Group A consisted of children whose parents had access to mobile phones for receiving SMS messages. In Tanzania, 20 schools from one implementation district were included, with a random allocation of 10 schools to each group, allowing for a more traditional randomisation process.

This pre-pilot phase allowed us to assess the practicality of the interventions, familiarise the country teams with the A/B testing approach, and laid the groundwork for later A/B testing by allowing each country team to test specific adjustments for improving children’s foundational learning at a larger scale. The next phase focuses on generating evidence-based decisions to scale the most impactful strategies, reinforcing PAL’s commitment to data-driven improvements in education. The initial results from the pre-pilot testing show improvements in treatment groups across both countries. While the early data points are promising, the results are drawn from pre-post comparisons and are meant to guide further rigorous testing rather than serve as conclusive evidence of impact. In preparation for full-scale A/B testing, we have been implementing more systematic planning, sampling, and documentation in the upcoming phase to further refine and optimise the interventions.

Planning for the pilot phase

Although the scale of the My Village 2 project is smaller than My Village 1, covering 15 villages in Nepal and 20 villages in Tanzania, we are building on the valuable lessons learned from the pre-pilot phase of A/B testing. With improvements in the delivery of project elements, along with enhanced data quality standards and management processes, we are well-positioned to engage all participants in My Village 2 in A/B testing.

We have identified specific, contextualised adjustments to evaluate in collaboration with the country teams. In Nepal, the team has chosen to integrate a peer tutoring component into their learning camps, where children with higher levels of foundational skills will tutor their peers at a lower level for part of each session. This tweak aims to enhance peer-led learning and improve overall engagement and outcomes. In Tanzania, the focus will be on supporting and supervising teachers through regular phone calls from village and teacher leaders. This mechanism is intended to ensure consistent guidance and support during the learning camps, enhancing the quality of instruction and the monitoring of progress.

The criteria for selecting these adjustments were based on their feasibility within the timeline of the My Village 2 project, the capacity of the implementers, the interest and support from country teams and local authorities, the low required resources for the implementation, and the potential for these adjustments to be integrated into regular education systems and scaled up for broader impact. With the data and lessons learned from A/B testing, we aim to refine and scale the most successful interventions, creating evidence-based strategies that can be adopted at a larger scale. This process also opens the door for broader advocacy with local education systems to integrate these methods into their regular programming, fostering long-term improvements in foundational learning.

Challenges faced

As with any rigorous testing initiative, one of the main challenges we encountered in the design of the A/B testing process was working with smaller sample sizes. With only 15 villages in Nepal and 20 villages in Tanzania in the My Village 2 project, the sample size in each group could be not-big-enough to detect subtle differences between the interventions.

To address this challenge, we have adjusted the study design and statistical methods. We have carefully calculated the power of the test 1, effect size2, minimum detectable effect (MDE)3, and intra-class correlation (ICC)4, to determine whether our study design could produce meaningful results given the sample sizes. For instance, the MDE was calculated to understand the smallest effect we could reliably detect with our available participants. We used strategies, such as covariate adjustment (ANCOVA), to control for baseline differences between participants and reduce the variability in the data. This allows us to maintain statistical power without needing to significantly increase the number of participants.

Lessons learned so far

Lesson 1: Importance of flexibility in design

Throughout our A/B testing efforts, one of the key lessons we’ve learned is the importance of maintaining flexibility in our design. As we faced constraints such as smaller sample sizes and limited resources, we had to continuously adjust our testing methods to fit the realities on the ground. By employing creative randomisation techniques and using covariate adjustment methods to optimise the reliability of our results, we were able to work around the constraints without compromising the integrity of the study.

Lesson 2: Value of local collaboration

Collaboration with local teams has been crucial to the success of our testing process. Involving country members in the design and implementation phases provided invaluable feedback that shaped the interventions and ensured they were contextually relevant. Their insights helped us identify feasible tweaks and ensured smooth operational execution. This collaboration also empowered the country teams to take ownership of the project, making the A/B testing process more effective and rooted in local realities.

Conclusion

The findings from My Village 1 and and the pre-pilot A/B testing have provided us with valuable insights into the potential impact of the interventions. These pre-post results are suggestive rather than conclusive. As we prepare for full-scale A/B testing in My Village 2, we will be able to rigorously test the most effective strategies and provide more robust evidence to support scaling and advocacy efforts. A/B testing has the potential to be an invaluable tool in our efforts to create scalable, evidence-based interventions that can make a real difference in improving foundational learning.

As we move forward, we are excited about the possibilities that data-driven decision-making will bring. Once the A/B testing results from My Village 2 are in, we will be better positioned to scale the most successful interventions, advocate for their adoption by local education systems, and enhance learning outcomes for children in various regions. The work ahead holds great promise, and we are eager to see the impact of our upcoming efforts.

Footnotes

1 Statistical Power: The probability that a test will correctly detect a true difference when one exists. Typically, a power of 80% is desired, meaning there’s an 80% chance of detecting an effect if it is present.

2 Effect Size: A measure of the magnitude of a difference between two groups. It indicates how much one group differs from another in the outcome of interest. Small effect sizes represent minor differences, while large effect sizes represent substantial differences.

3 The minimum detectable effect (MDE) is the smallest change or difference between groups that a study is designed to detect with a given level of statistical power.

4 Intra-Class Correlation (ICC): Indicates the degree of similarity between units within the same group. A higher ICC means more similarity within clusters, affecting data interpretation and required sample size.

Note: This blog was initially posted on the What Works Hub for Global Education website