Happy children in a primary school in Lao PDR. CREDIT: GPE/Stephan Bachenheimer

The authors* of The Handbook on Measuring Equity in Education also contributed to this blog

It is something we have come to see as self-evident: education is a fundamental right, and without it, our lives – and indeed our world – would be greatly diminished. It is something we even take for granted.

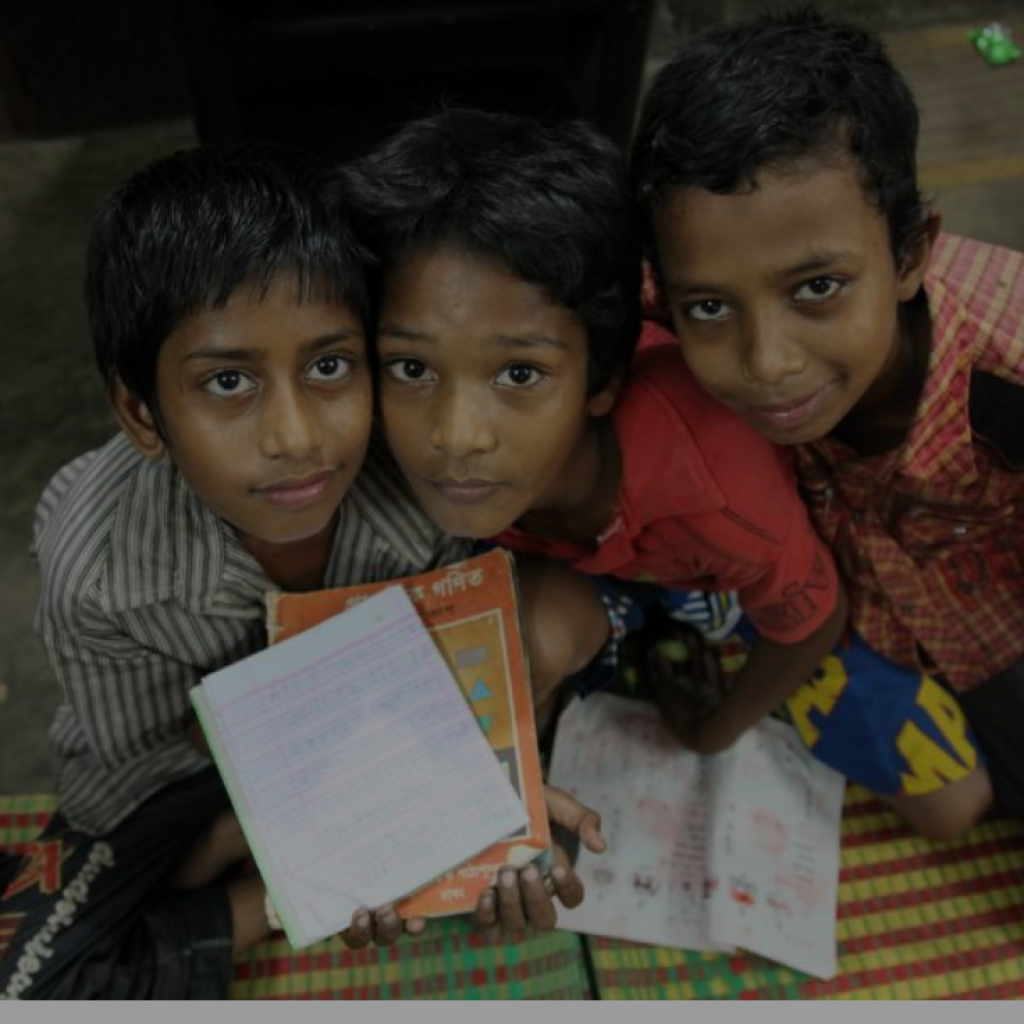

But as the most recent data show, one in every five children, adolescents and youth worldwide is denied this right, shut out of the education that could, or should, transform their lives. They are often the poorest of the poor, the children with disabilities, the refugee or migrant children. They are often girls, but in some countries – and at some levels of education – they are also boys.

Too many marginalized children are invisible

These children are taught a harsh lesson about their own exclusion – and their own worth – at a tender age. They see more fortunate children going to school, and coming home from school. They see other children with textbooks. They hear children talking about what they learned today, and what they will learn tomorrow.

How much more bitter that lesson becomes when they realize that they are excluded because of who or where they are. In effect, an accident of birth means that they are the losers in the education lottery. As if they didn’t have enough problems, they are also invisible in the data. We simply don’t know enough about them.

Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) calls for inclusive and equitable quality education for all, spanning not only gender parity in learning but also equitable educational opportunities for people with disabilities, indigenous peoples, disadvantaged children and others who are at risk of exclusion from education. In other words: no exceptions, no exclusions, and nobody left behind. But this goal cannot be achieved without better data and analysis to monitor progress for the most marginalized populations.

New handbook helps find the most disadvantaged from education

The new Handbook on Measuring Equity in Education, produced by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), the FHI 360 Education Policy Data Centre, Oxford Policy Management and the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge, provides practical guidance on the calculation and interpretation of indicators designed to target the most disadvantaged groups.

It is intended for anyone involved in the measurement and monitoring of equity in education, especially those concerned with national policymaking. It addresses the current knowledge gaps and provides a conceptual framework to measure equity in learning, drawing on examples of equity measurement across 75 national education systems.

Two key principles: impartiality and equality of condition

The handbook sets out what it actually means to measure equity in learning, recognizing that equity itself is a political issue and cannot be isolated from political choices. It focuses on two key principles – impartiality and equality of condition – that could gain traction and shape measurement efforts.

Impartiality zooms in on the idea that it is unfair to discriminate by characteristics such as gender, wealth or ethnicity when it comes to the distribution of education. Measures of impartiality quantify the extent to which an educational input or outcome differs by such characteristics.

Equality of condition focuses on the dispersion of education in the population, without regard for differences between groups. While perfect equality of condition in education outcomes might not be possible or desirable, wide or growing gaps between the least and most educated are likely to be a cause for concern.

The handbook introduces visualization and measurement techniques related to impartiality and equality of condition, the requirements for the use of underlying data to measure both, and the advantages and disadvantages of each technique for generating insights into the magnitude and nature of any inequality.

It provides solid examples of national efforts to track progress towards equity in both educational access and learning, highlighting positive country examples and stressing the need to include a wider range of dimensions of disadvantage in education plans.

Allocating education funding more equitably

Finally, the handbook examines government spending on education to reveal who benefits, who misses out, and how resources could be redistributed to promote equity. It points out that in many countries, the children and young people who are the hardest to reach are often the last to benefit from government spending. It is simply more expensive to ensure their quality education, given the cost of measures to tackle the root causes of their disadvantage, from poverty to discrimination – and this should inform the distribution of resources.

While equal funding means the same amount of money for each student or school, equitable funding means additional resources for the most disadvantaged children to ensure that every child can enjoy the same educational opportunities. As the handbook argues, progress towards SDG 4 demands the equitable distribution of resources within education systems, with the most disadvantaged receiving the largest share of government resources, and paying the smallest share from their own pockets. It highlights national education accounts as an important way to track progress, and the funding formulae that are being used across a number of countries.

The new handbook has been inspired by the urgent need to position educational equity at the heart of global, national and local agendas to promote access and learning for all children, young people and adults. With countries under pressure to deliver data on an unprecedented scale, the Handbook also recognizes that no country can do this alone, making a strong case for greater cooperation and support across governments, donors and civil society.

The delivery of equitable quality education is the only way to end the cruelty of the education lottery, with its winners and losers. It underpins the world’s development goals, from poverty reduction to the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies. We hope that the handbook will help to translate the commitments made to equitable education under SDG 4 into tangible action for all those currently on the sidelines.

*The authors are presented in the order of their respective chapters: Chiao-Ling Chien and Friedrich Huebler of the UIS; Stuart Cameron, Rachita Daga and Rachel Outhred of Oxford Policy Management; Carina Omoeva, Wael Moussa and Rachel Hatch of FHI 360; Ben Alcott, Pauline Rose and Ricardo Sabates of the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge as well as Rodrigo Torres of UCL Institute of Education.