This week we released a film called Every Child Counts (And Reads): Measuring Learning for All (there’s also an abbreviated version and the French version, if you’re interested), which explores an innovative approach for measuring what children have learned and making it matter to parents and policymakers alike.

Three years ago I was in rural India directly participating in one of these surveys in the almost unbearable heat of summer. I was with two Indian colleagues who were hard at work mapping a village in Uttar Pradesh under the direction of the village headman. We were squatting in the shade but there was no escaping the hot, humid air.. A crowd formed around us as my colleagues sketched the village’s different neighborhoods on the pavement with chalk. The crowd moved quickly from bystanders to participants, offering advice with hand gestures and rapid Hindi—“No, no, the school is across the road from the well, not next to it!” Or at least that’s what I imagined them saying. My Hindi was—still is— next to nonexistent, but there was no mistaking the interest they took in us and our map.

Eventually the villagers asked us why we were there. Why were we drawing a map of the village? What had we come here to do? My colleague explained that we were doing a survey. We wanted to see if the children of this village could read.

That day was actually a dress rehearsal for a much larger survey. My colleagues were preparing for the Annual Status of Education Report, or ASER (pronounced ah-sir) for short. ASER means “impact” in Hindi and is aptly named since the goal of the survey is to see what impact education is having.

This year, it’s likely that more children will finish elementary school than ever before. This is not just because there are more fifth graders in the world than ever before. It is also because today most children go to school, no matter where in the world they were born. In an extraordinarily short amount of time the world has managed to make the opportunity to go to school nearly universal.

But what about the opportunity to learn?

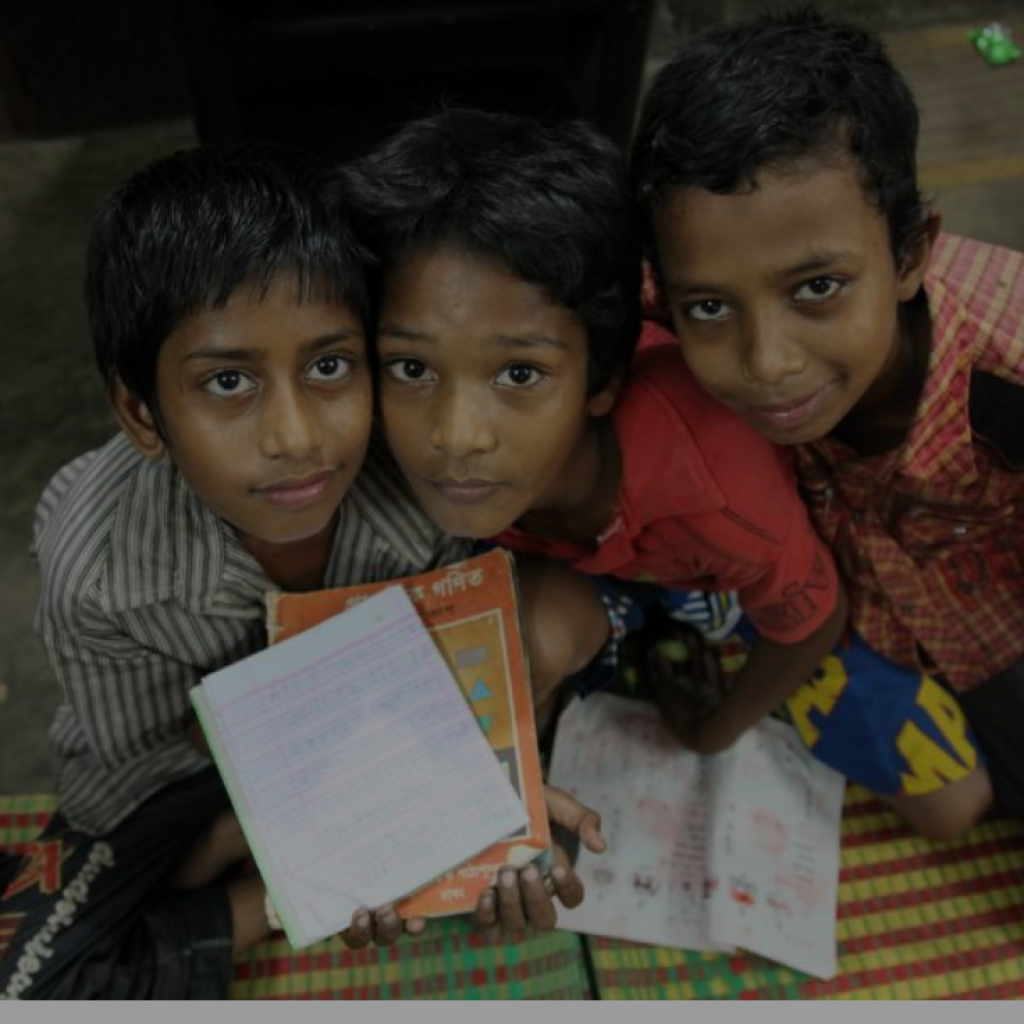

For a long time people were so focused on counting whether or not children were attending schools that they did little accounting for how much learning was going on. ASER is an effort to address that gap. So are similar surveys like Uwezo in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, Bèekunko in Mali, Jàngandooin Senegal, and ASER Pakistan. Collectively these efforts assess over one million children, every year, in their homes. As my colleague Rukmini Banerji, Director of ASER, points out, the surveys help “demystify learning for mothers, fathers and family members—especially those who are not literate or do not have much schooling—and make it possible to see what learning looks like.” The findings show that a mere half of fifth graders in India and Pakistan can read, and a mere 20% of fourth graders in Mali can subtract. This has put pressure on governments to place due attention not only on whether or not children finish school, but whether or not they leave with the skills they need to thrive.

To complement the video released this week, the photo essay in the link below explores these assessments in progress, as captured during that sweaty summer day in Utter Pradesh and other visits to the field.

Click here to view the photo essay on the Hewlett Foundation Blog