Naliaka’s Long Journey to Freedom Through Literacy

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the World Literacy Day, Rosa Naliaka celebrates two important milestones: her 30th birthday, and winning her war against illiteracy. Nowadays, by 7.00 am Naliaka has caught up with her e-mails, updated her Facebook page, and connected with friends on WhatsApp and Instagram. Until recently, Naliaka could be counted amongst the 6.8 million Kenyans unable to read or write. Today she has exited these statistics, and behind this emancipation is an inspiring story.

Longing to Learn

Born in Busia County in Western Kenya, Naliaka dropped out of school when she was in Grade 3 after both her parents died. An only child, Naliaka was sent to live with her grandmother for about a year before she, too, passed away. When a sympathetic neighbour agreed to take Naliaka with her to Nairobi, she built up her hopes of a better life. Arriving in Kibera (East Africa’s largest slum) she followed other kids to the nearby Gatwekera school, and peeped through the mud-wall holes, listening to the children as they learned.

At the age of 12, Naliaka started looking for work to support her foster family. She worked in many places, cleaning clothes for people and doing menial jobs. In one place, she worked for five months without pay, and when she asked for it, her employer responded, “Were you not eating at my place?” At the tender age of 14, she became a mother and her life changed completely. “I put up with this man for a while,” Naliaka said about the father of her daughter. “One day, he discovered that I could not even write my name, and he chased my daughter and I away”. After a while, Naliaka met another man, and after moving in together she quickly fell pregnant again. “This man was very educated, and I really revered him. One day, he discovered that I could actually not even read an SMS. I arrived home one evening from work and found my children crying in an empty house. He had packed his things and deserted us. I never saw him again.”

Everyday Hurdles

One of Naliaka’s employers asked her to open a bank account so she could be paid by cheque. Unable to read the forms that would allow her to open a bank account, she relied on the security guards. She would pick up the form, take it to them and request help. She watched as they wrote things on the form and then they told her: “Panga line hapa” (queue here). Once the bank issued her with an ATM card, Naliaka would call her brother every time she needed to withdraw. “He would come when available, then we walked to the ATM. He punched in some things, and the transaction would be complete”. What disturbed her most is that she lacked privacy; her private messages and bank records had to be read by another person.

Among the most challenging hurdles for Naliaka was the expectation that she should check her children’s homework. Unable to read what they had written, she would take the books, peruse through briefly and respond “It’s good!” Then one day, her daughter came back home furious. “Mum, why did you lie to me? You told me that I had done good work but when the teacher checked, I failed everything!”

A Fresh Start

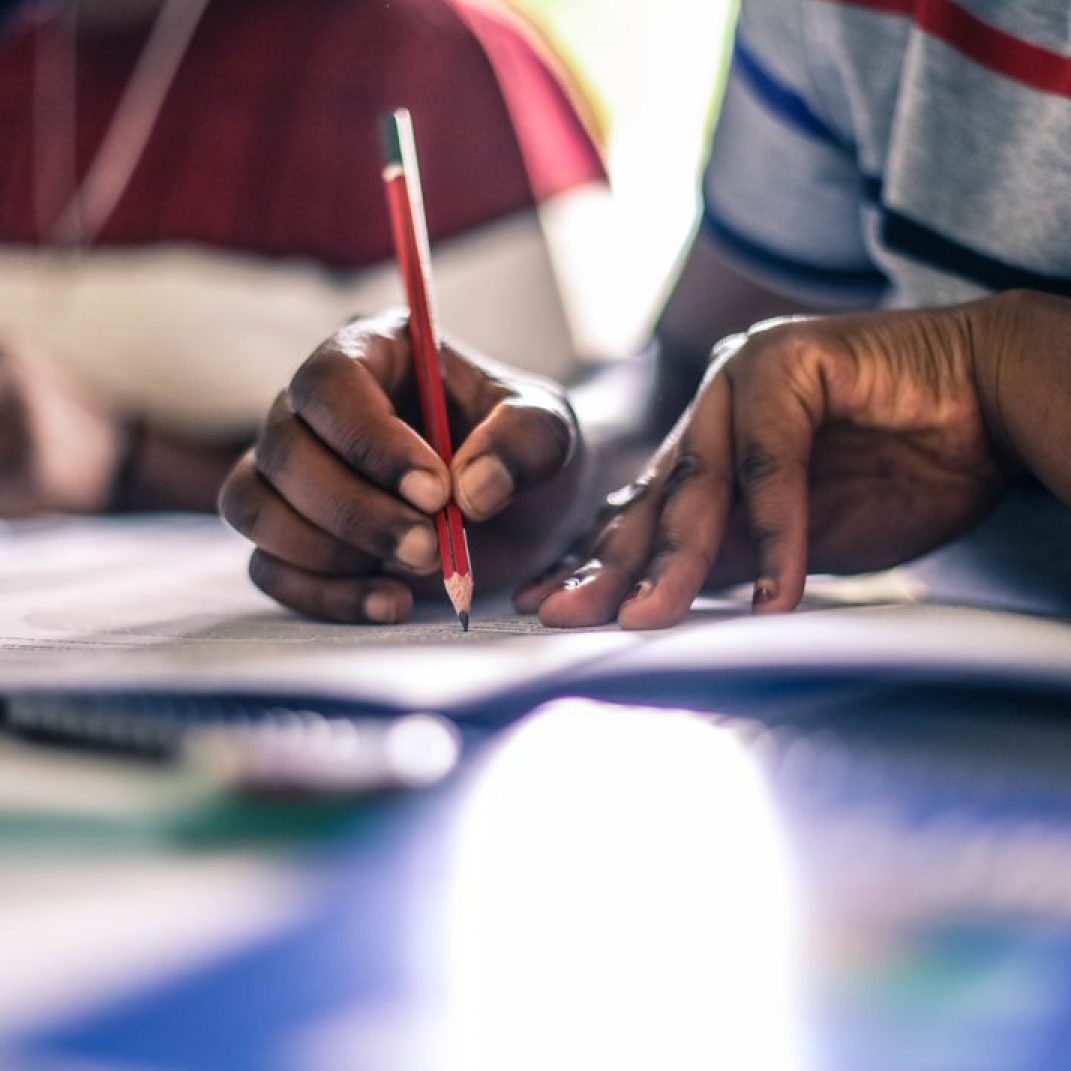

One day, her mother’s sister talked to someone she knew about Naliaka’s struggle. The lady employed Naliaka at her organization to clean and prepare lunch. “She accepted me as I was, and even assigned one female employee to teach me how to read and write whenever I completed my work” Naliaka happily recalls. This experience was transformative. “She sat patiently with me, showed me how to hold a pen and how to write letters of the alphabet. They later paid for me to attend an adult education classes!”

She joined Grade 2 in a class of 25 other adults. “I discovered that even much older women could not read. They started by showing us the basic things – using M-pesa, banking and writing letters.” However, the new life of juggling the responsibilities was not easy. “I would wake up at 4 a.m. in the morning, complete some housework, go to the office, do the cleaning and cooking, and settle on homework before 1 pm. I would then rush back home to cook for the children, then go to school from 4-8 pm. I would return home late, check on the girls, then we slept. This was my daily routine for nearly 5 years” recalls Naliaka.

The hardest challenge was concealing her schooling life to her children, relatives and friends, given the stigma attached to adult learning (dubbed ‘Ngumbaru’ in Kenya). She left all her books at school, and only carried her homework book in her handbag. When she had urgent homework, she completed it at night whilst her girls slept. But one day she broke the news to them that she was registering for her end of primary examinations. “My daughters were so elated! They would even wake me up at night to revise, as they attempted to help me”. Naliaka scored 295 out of 500 marks. “It is not the marks that delighted me, but the fact that I could now speak English, read my SMS messages, chat on Facebook and above all, I had the ticket to continue to secondary school”.

Freedom

For Naliaka, literacy is real emancipation. She now uses a computer and proudly has an e-mail address. Like many of her friends and colleagues, she is active on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp. “I lead a free and enjoyable life now. I bank online and conduct the M-pesa transactions myself. I enjoy my own privacy and can help my children with their homework. I have continued with secondary education, and cannot wait to hold that coveted secondary education certificate in my hands. When I finish, I will follow my catering passion and secure some capital to start my own catering business. I want to inspire my daughters to reach even greater heights”.